Why does zsteg not work on JPEG files?

If you’ve been playing CTFs for some time like me, you would be somewhat familiar with what Steganography is (or at least know what hail mary stego tools to throw image files at to hopefully obtain a flag).

Yesterday, when I was trying to write a simple steganography challenge for a beginner CTF, I faced some problems where I tried to encode LSB data into a JPEG image file but did not get the same data back after decoding.

I also noticed that zsteg doesn’t take in JPEG files (something i’ve always encountered in past CTFs but never stopped to consider why that is the case). Hmm, interesting.

Before I explain my findings, let me provide some context for any beginners here

Dissecting a sRGB Image

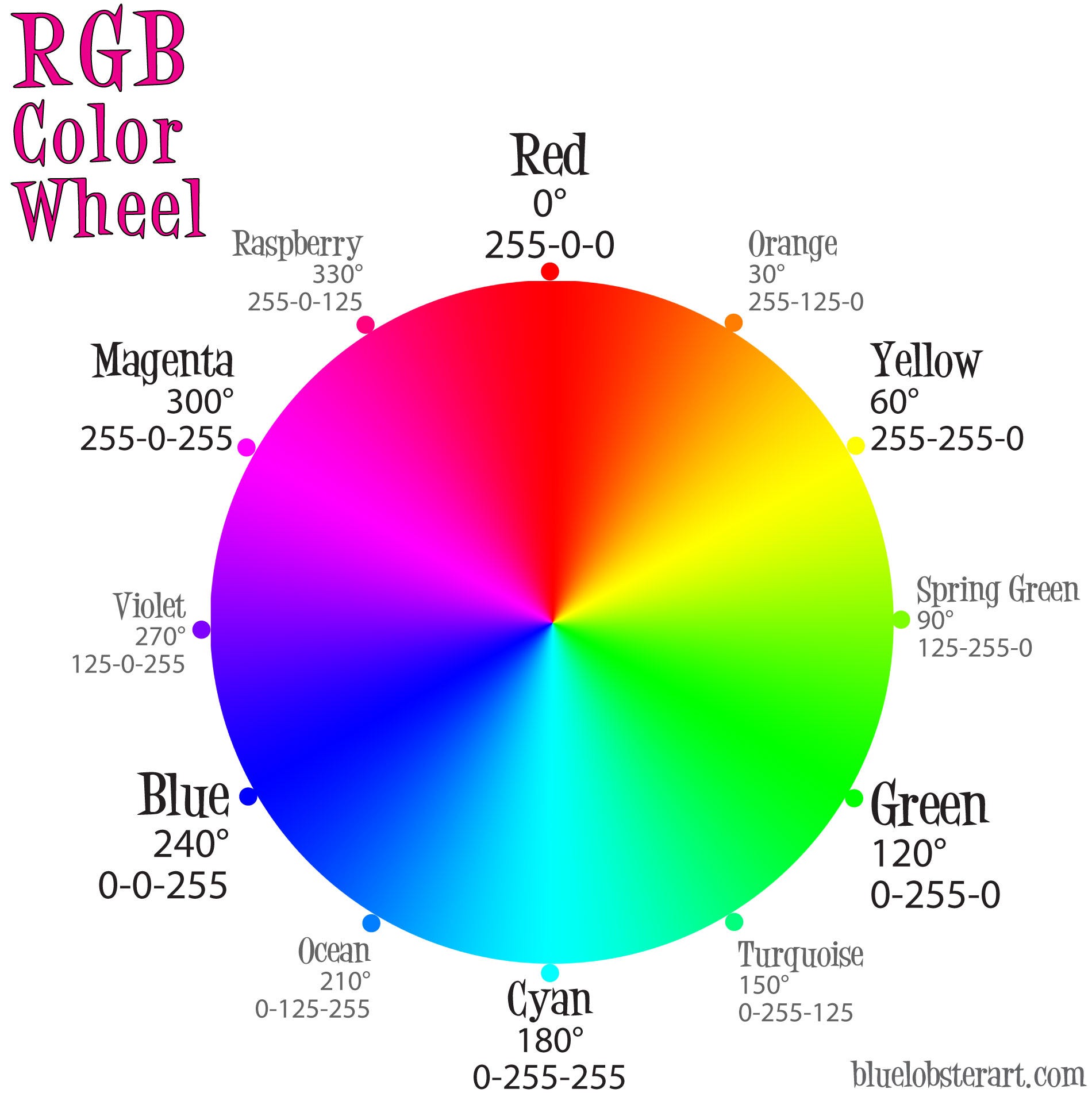

Fundamentally, images are made up of a bunch of small pixels that displays a single color. The more pixels in an image, the higher the resolution and vice versa. Specifically, the vast majority of digital images on the internet uses the sRGB (standard Red Green Blue) color space.

To display a color, each pixel has a set of 3 values (Red, Green and Blue) of values between 0 to 255. It is easy to deconstruct an image into its pixel values programatically

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

from PIL import Image

im = Image.open("./srgb_wheel.jpg")

pixels = list(im.getdata())

print("First 10 pixel values:", pixels[:10])

# Output:

# First 10 pixel values: [(255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255), (255, 255, 255)]

As you can see, the first 10 pixels in the image above are (255, 255, 255) which represent the (R, G, B) values respectively, and represents a white pixel.

Bit Plane Steganography

Each value R, G and B are represented from 0-255, which is nicely 8 bits of information.

| value | bits |

|---|---|

| 0 | 00000000 |

| 1 | 00000001 |

| … | … |

| 127 | 01111111 |

| 128 | 10000000 |

| … | … |

| 254 | 11111110 |

| 255 | 11111111 |

The key distinction to make here is that the rightmost bit is also known as the Least Significant Bit (LSB) because it has the least effect to the overall magnitude of the number.

In layman terms, if we were to change the LSB value from 0 to 1, the value does not change much (i.e. 0b00000000 and 0b00000001 is 0 and 1 respectively).

Conversely, the leftmost bit is also known as the Most Significant Bit (MSB) because it has the most effect to the overall magnitude of the number.

In layman terms, if we were to change the MSB value from 0 to 1, the value changes significantly (i.e. 0b00000000 and 0b10000000 is 0 and 128 respectively).

LSB Steganography

Since LSB has little effect on the magnitude of the number, changing the LSB values of the pixels of an image will change it so slightly that it’s likely not visible to the human eye.

Let’s look at the following example

Are you able to tell the difference between these 2 images? The image on the left contains the hidden string HEY that is embedded into the LSB value of the image!

Since there are 9 pixels and each pixel have 3 values (R, G, B), there are a total of 27 color values in this image. If we were to hide data in the LSB of each image, we will be able to hide 27 bits of data which is sufficient to hold up to at least 3 bytes (24 bits) of data.

Here’s the script that encodes the data and also decodes it back.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

from PIL import Image

def encode(image_path, message, output_path):

img = Image.open(image_path)

pixels = list(img.getdata())

# Convert message to binary

binary = ''.join(format(ord(c), '08b') for c in message)

# Encode in LSB

new_pixels = []

idx = 0

for pixel in pixels:

if idx < len(binary):

r, g, b = pixel

if idx < len(binary):

r = (r & ~1) | int(binary[idx])

idx += 1

if idx < len(binary):

g = (g & ~1) | int(binary[idx])

idx += 1

if idx < len(binary):

b = (b & ~1) | int(binary[idx])

idx += 1

new_pixels.append((r, g, b))

else:

new_pixels.append(pixel)

encoded_img = Image.new(img.mode, img.size)

encoded_img.putdata(new_pixels)

encoded_img.save(output_path)

print(f"Message encoded in {output_path}")

def decode(image_path):

img = Image.open(image_path)

pixels = list(img.getdata())

# Extract LSB

binary = ''

for pixel in pixels:

r, g, b = pixel

binary += str(r & 1)

binary += str(g & 1)

binary += str(b & 1)

# Convert binary to text

message = ''

for i in range(0, len(binary), 8):

byte = binary[i:i+8]

message += chr(int(byte, 2))

return message

encode('3x3_pattern.png', 'HEY', '3x3_pattern_encoded.png')

print("Decoded:", decode('3x3_pattern_encoded.png'))

MSB Steganography

Now let’s look at what happens if we were to encode our data in the Most Significant Bit (MSB) instead of the LSB.

The image on the left has the string HEY encoded into the MSB of the image pixel values.

As you can tell, the image has obviously been modified since the RGB values has changed significantly. This is why, while it is possible to encode data in the MSB pixels, it is rarely done since it is very obvious to the human eye.

Visualizing the bit planes

By now you would have come to the conclusion that data can be hidden in any of the bits of the image. To make this even harder, sometimes we can hide data only in the LSB of the Green pixel values, or even hide them in the LSB of the Red pixel, 2nd bit of the Green pixel values and 3rd bit of the Blue pixel values and so on.

You get the idea, there’s so many combinations of how data can be hidden in the different bits or even different color planes. Is there an easy way to visualize any possibly encoded data in the pixels?

Well, we could techncially do: for each color plane, for each bit, output an image where the RGB values are 255,255,255 or 0,0,0 depending on whether the bit is 1 or 0.

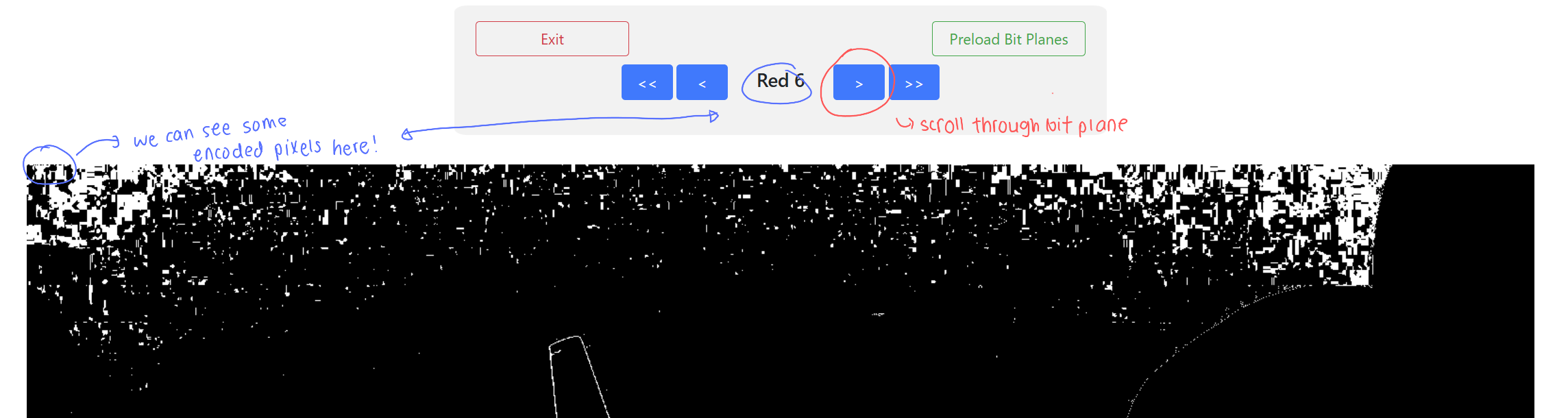

So for a regular RGB image, we will have 24 images that corresponds with a bit for each of the color planes (8 bits per plane). Let’s try to analyze this (extremely cursed) CTF challenge where data is embedded into multiple bits in different planes.

Clearly, we can see that the first few pixels (top left of the image) looks funny, and is likely hiding bits of information. This is where I introduce StegOnline which is an amazing tool that dissects an image into the different bit planes.

StegOnline allows you to scroll through bit planes, where we can look for suspicious encoded pixels (typically on the top left of the image).

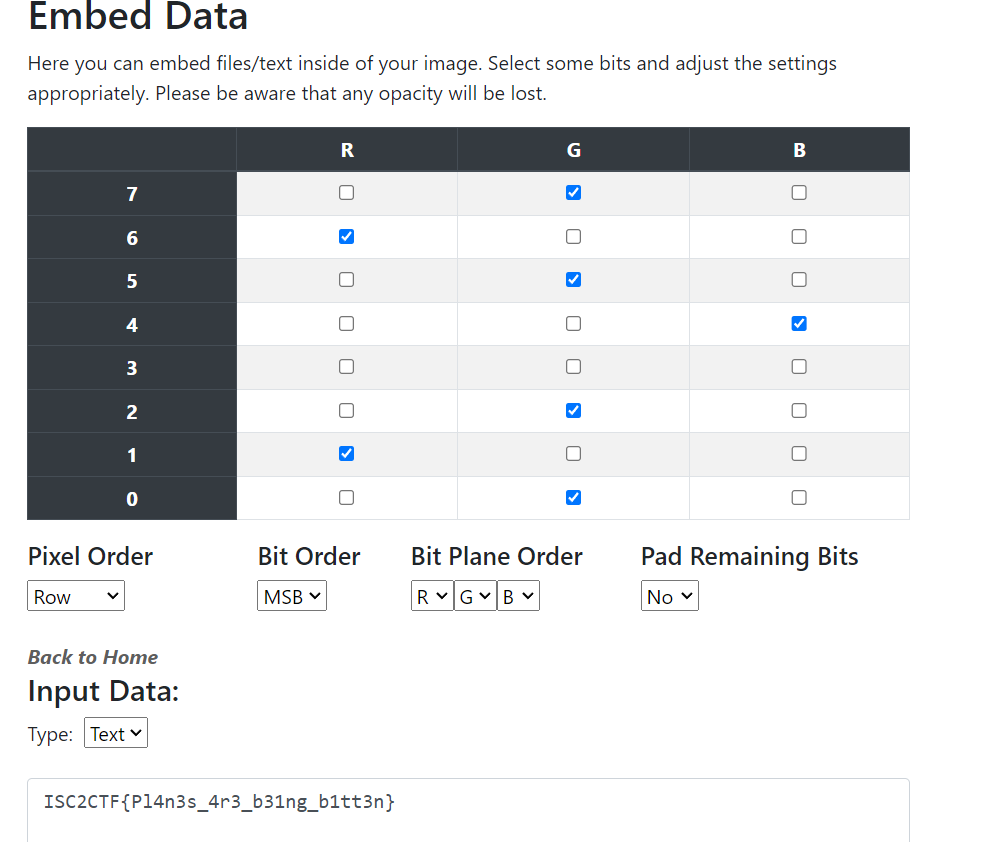

As we can see above, there are some encoded data in the red plane on bit 6. If we continue scrolling we can find more encoded pixels in the following planes: R6, R1, G7, G5, G2, G0, B4.

Then in StegOnline, we can go to the Extract Files/Data to extract the hidden data from these planes, which would look something like this.

zsteg

zsteg is a command line tool that automatically tries to extract data from many different combinations of bit planes, looking for strings (at least length 8 strings by default) and any files that it might find. This is also the tool that AperiSolve uses to extract LSB data from images.

1

2

3

❯ zsteg 3x3_pattern_LSB_encoded.png -n 3

b1,rgb,lsb,xy .. text: "HEY"

b3,g,msb,xy .. text: "<Fp"

However, I’ve noticed that zsteg does not work on JPEG files.

1

2

❯ zsteg test.jpg

[!] #<ZPNG::NotSupported: Unsupported header "\xFF\xD8\xFF\xE1\x00\xBCEx" in #<File:test.jpg>>

In fact I’ve never really seen any LSB steganography done with JPEG files. Interesting :)

Can we do Bit Plane Steganography on JPEG?

Ok… I’ve steered too far off from what the main point of the post, but I felt like that was necessary and interesting context to actually get here. So far all the bit plane steganography we’ve done is using the PNG image format. What about JPEG image format, can we encode LSB data inside a JPEG file?

Consider the python script below, which create an array of RGB values and saves it into a JPG file. The same JPG file is re-opened and the RGB values is read. We would expect that the values that we print out should be the same set of values that we created the image with.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

# create 3x3 image where pixels are RED GREEN BLUE RED GREEN BLUE RED GREEN BLUE

colors = np.array([[[255, 0, 0], [0, 255, 0], [0, 0, 255]],

[[255, 0, 0], [0, 255, 0], [0, 0, 255]],

[[255, 0, 0], [0, 255, 0], [0, 0, 255]]], dtype=np.uint8)

img = Image.fromarray(colors)

img.save('looping_rgb.jpg', 'JPEG')

# let's reopen the image to view the values

img = Image.open("looping_rgb.jpg")

pixels = list(img.getdata())

print(pixels)

Surprisingly, the output of the script above is

1

[(90, 91, 0), (166, 167, 40), (5, 0, 252), (90, 91, 0), (166, 167, 40), (5, 0, 252), (90, 91, 0), (166, 167, 40), (5, 0, 252)]

and we get this image

The reason behind this weird phenomenon is compression. JPEG is a lossy file format (unlike PNG which is lossless), which means that some data is permanently discarded, typically data that is not perceptible to the human-eye for the purpose of reducing file size.

This means that given a JPG file, we cannot determine what is the exact RGB values that the file was originally saved with. Similarly, many different set of RGB values can be compressed into the same result.

This is why bit plane steganography is not effective in JPEG files since our encoded LSB data is likely to be discarded due to JPEG lossy nature.

The Final Challenge

The idea behind JPEG being lossy is that the data that it discards would typically not be perceptible to the human eye. Previously, we discussed how LSB have very little visible effect on images, this is EXACTLY the kind of data that will be likely to be discarded by the JPEG lossy compression!

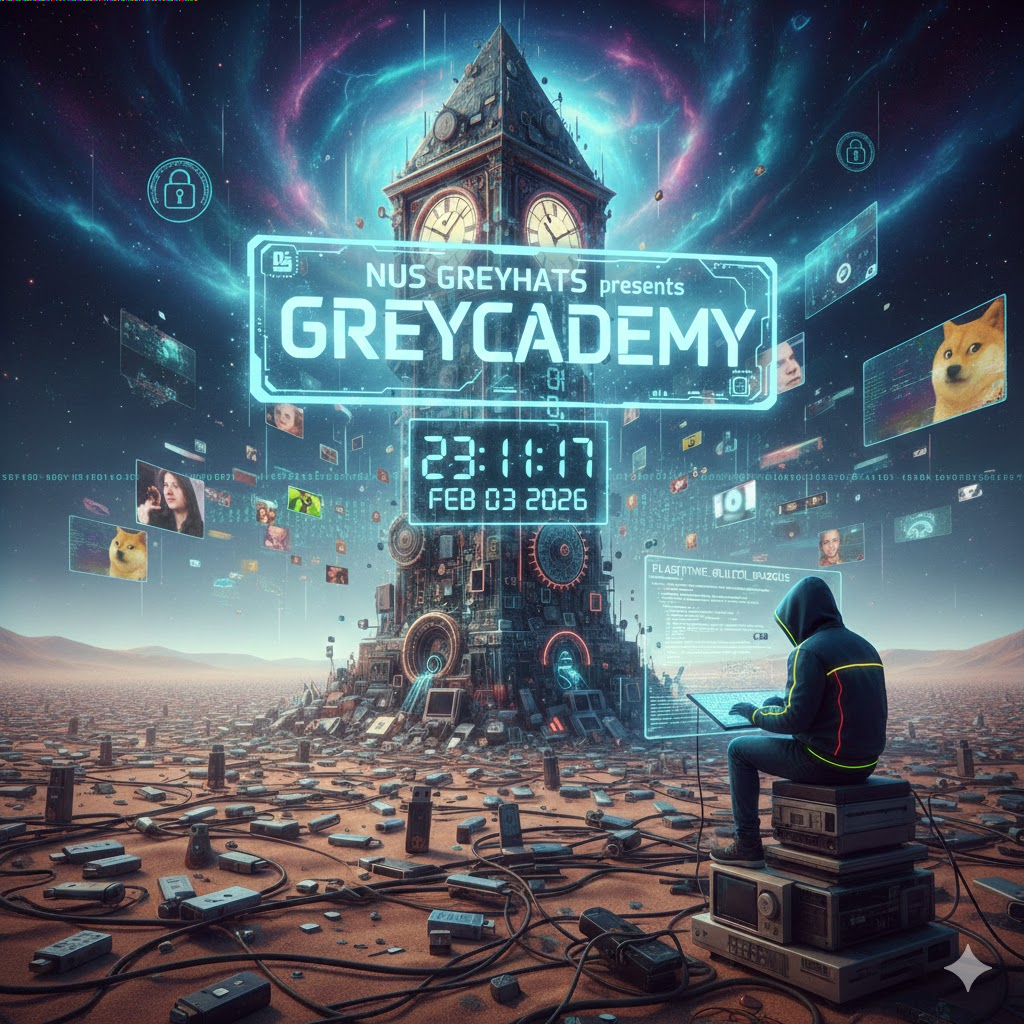

With that in mind, since MSB have very visible effects on images, it is less likely to be discarded by the JPEG lossy compression. In that case, we can possibly still encode data in the MSB bits of our JPEG image.

Here’s the final challenge I made with a flag encoded in the MSB of the JPEG image. Feel free to give it a try, the source code to encode and decode data can be found here.

Afterword

This was meant to be a very short post to just share about the idea behind why we cannot do LSB steganography in JPEG files due to it being lossy, but it turned out to be much longer than I expected – I guess I find it hard to skip over fundamental concepts that would provide important context to the main idea which leads to be being rather naggy.

This has been something quite different from my typical posts, hope you enjoyed.