Control Flow Obfuscation — What happens if we modify callee-saved registers? 🙈

I’ve always had much appreciation for all the low-level things from assembly to compilers and more. In my pursuit to better understand these mechanisms, I’m often left with many questions on what happens if we challenge the different assumptions and conventions that our compilers are built upon.

In this post, we will question the following conventions and break some assumptions made by disassemblers/decompilers to obfuscate control flow and hide code!

What happens when we break compiler conventions?

What happens if you modify registers that do not belong to you?

Proof of Concept (PoC)

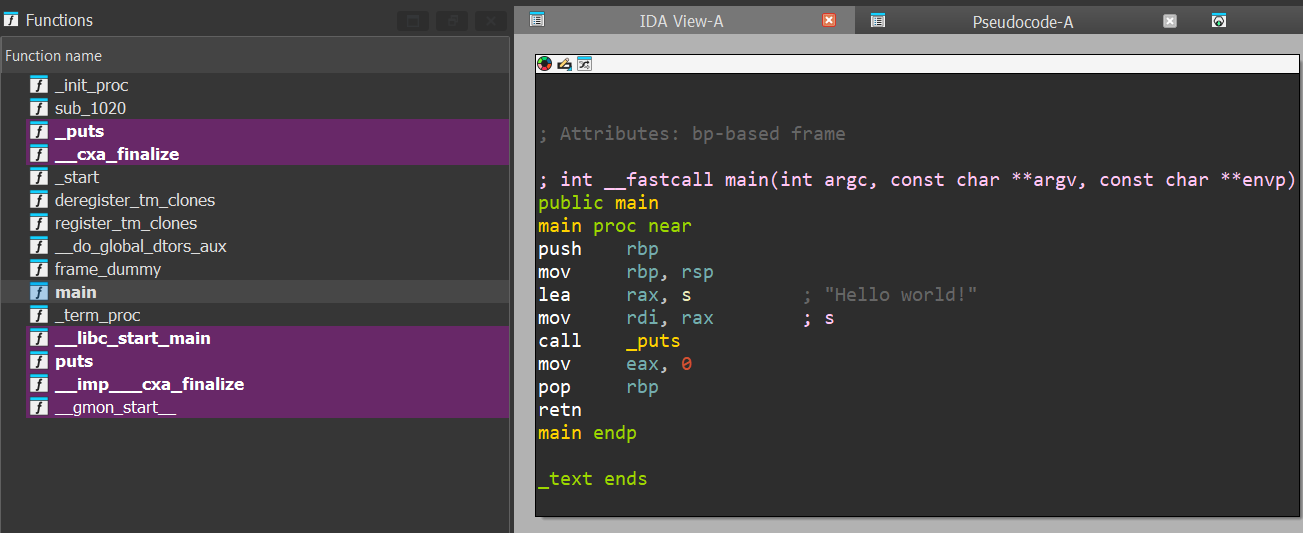

Before we dive into the details, let me first share a snippet of the proof of concept! You can find the binary here.

As you can see, the program is pretty small and the main function does nothing except put("Hello world!") and it does not have many defined functions as well.

disasembly of the main function

disasembly of the main function

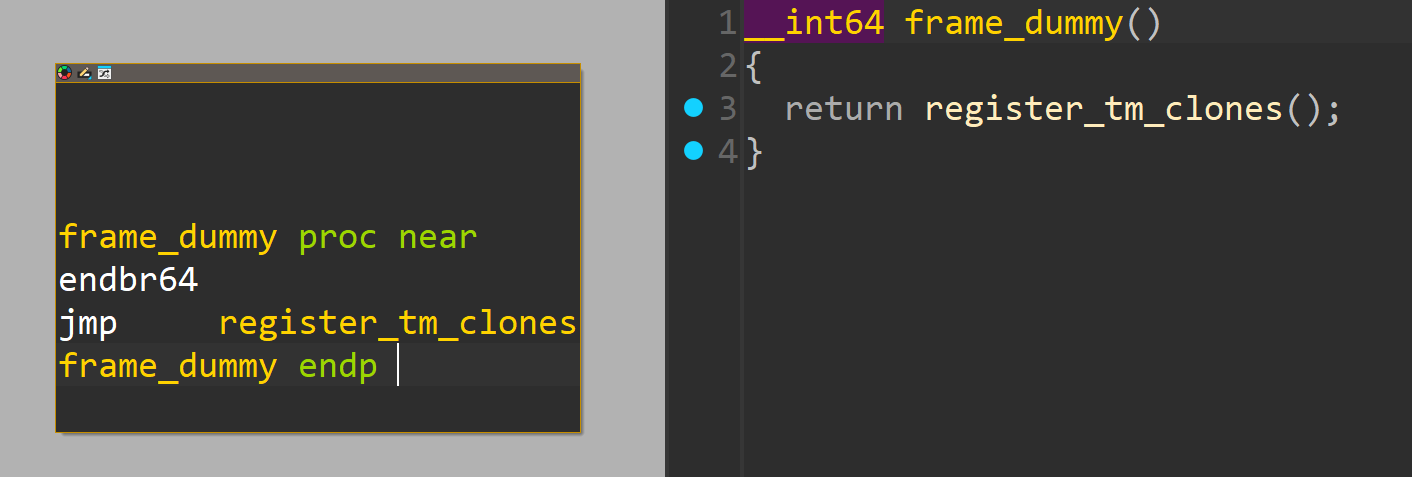

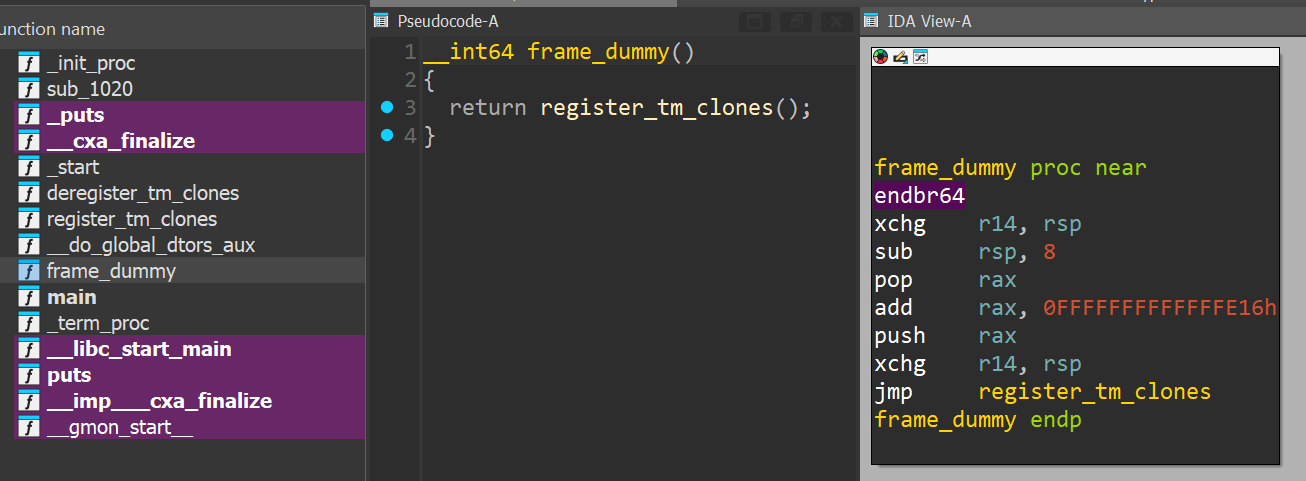

Probably, the most “out of the ordinary” function would be frame_dummy that is typically overlooked since it exists in most ELF binaries as some sort of a placeholder function.

disasembly of the frame_dummy function

disasembly of the frame_dummy function

However, if you run the program with the correct parameters, it will print nice!.

1

2

3

4

5

6

❯ ./helloworld.elf

Hello world!

❯ ./helloworld.elf sctf{going_beyond_hello_world_1z2ket65cx3sdxfjb}

nice!

Hello world!

Where in the code does it even check for the command line argument, and prints nice!??

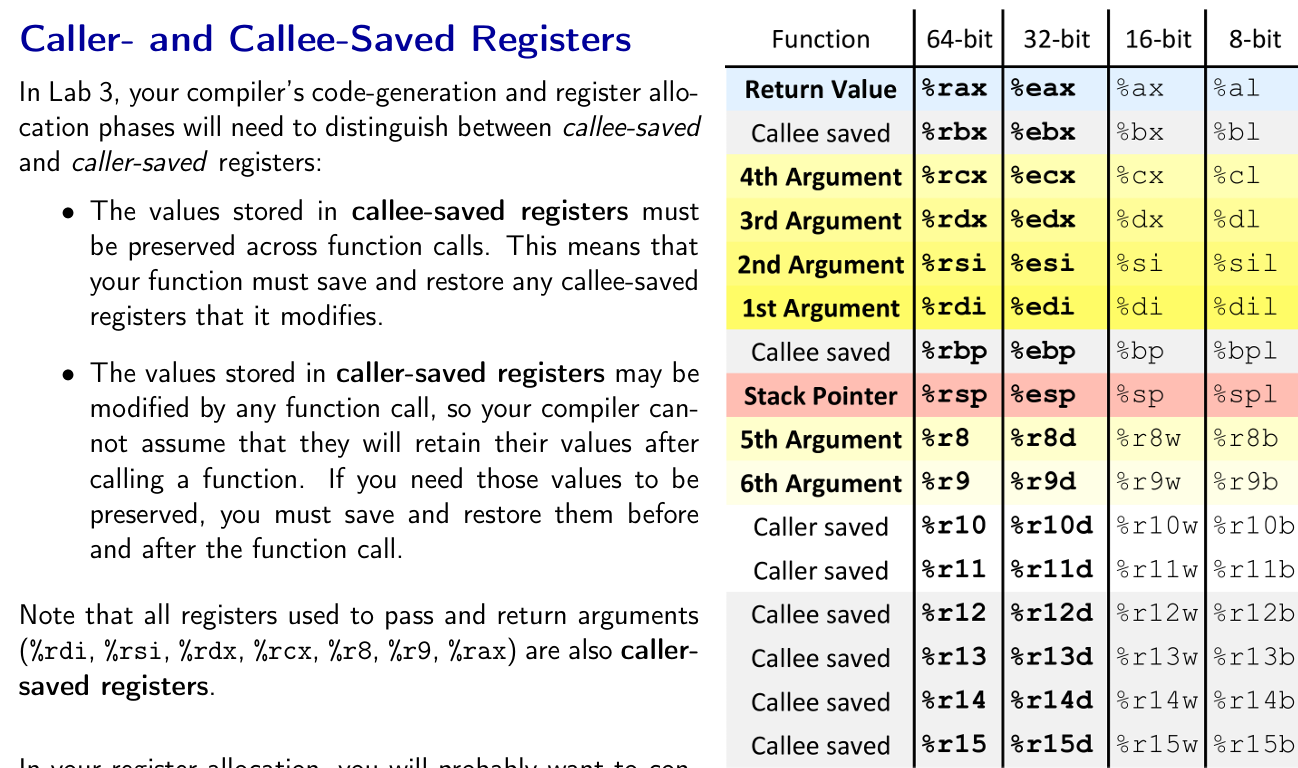

Compiler Convention on x64 Registers

For those with some assembly knowledge, we often know of registers simply as a variable that stores a value.

Some registers are known as special-purpose registers,

RIP: Holds the address of the next instruction to be executedRSP: Holds the address of the top of the stack frame (modifiable viaPUSH/POP)

while the rest are often simply called general purpose registers that we can also classify as caller/callee-saved registers.

reference: Notes from CMU Compiler Design Class

reference: Notes from CMU Compiler Design Class

Variables in our programs are typically either stored on the stack or in registers.

Variables in the stack will need to be read and updated through stack dereferences which becomes inefficient for variables that are frequently used throughout a function.

As such, callee-saved registers are sometimes used by the compiler to improve efficiency of the program.

Sometimes, caller-saved registers are also called volatile registers since the value of these registers are volatile and may be modified after a function call.

Conversely, callee-saved registers are also called non-volatile registers since the values of these registers are not modified after a function call.

Case Study: Calling constructors in Ubuntu’s GLIBC

This idea for obfuscation first came to mind when I was debugging GLIBC internals one day, specifically how constructors are called from __libc_start_main. Here’s the snippet of code responsible for calling the chain of constructors.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

; snippet of assembly code taken from __libc_start_main (ubuntu glibc 2.35)

loc_29EA8:

mov rdx, [rsp+48h+var_48]

add r14, 8 ; get next constructor

loc_29EB0:

mov [rsp+48h+var_48], rdx

mov rsi, r12 ; prepare argv

mov edi, ebp ; prepare argc

call qword ptr [rcx] ; call the constructor

mov rcx, r14

cmp [rsp+48h+var_40], r14 ; checks if any constructors left

jnz short loc_29EA8

Essentially, there are 3 callee-saved registers used here.

| register | purpose |

|---|---|

| EBP | argc - the number of command line arguments the program is executed with |

| R12 | argv - the list of command line arguments the program is executed with |

| R14 | the address where the list of addresses of the constructors are stored |

Additionally, var_40 stores the address of the last constructor in the list of constructors (defined in .init_array) and var_48 stores the pointer to the list of environment variables (aka char* envp[]).

The assumption here is that these registers will not be changed by the constructor functions. However, if we are able to modify r14, we could possibly repeat constructor functions or even call a different function by writing into R14!

Endlessly looping our constructor

By analyzing the assembly above, we can see that it is running in a loop where r14 is the loop index and r14 != var_40 is the terminating condition.

We can modify r14 -= 8 to make it call the same constructor over and over again!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#include <stdio.h>

// r14 -> pointer to constructor array

// r12 -> pointer to argv

// ebp -> argc

int __attribute__((naked)) __attribute__((constructor)) func1() {

write(1, "func1 called\n", 14);

__asm__(

".intel_syntax noprefix\n"

"sub r14, 8\n"

"ret\n"

".att_syntax\n"

);

}

int main() {

puts("hello world");

}

If we try to compile and run the above function, it will re-run the constructor and print func1 called forever.

Call a different function

If we go through an extra step to modify the pointer within r14, we can achieve calls into other functions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

#include <stdio.h>

// r14 -> pointer to constructor array

// r12 -> pointer to argv

// ebp -> argc

void __attribute__((used)) secret() {

puts("secret");

}

int __attribute__((naked)) __attribute__((constructor)) func1() {

__asm__(

".intel_syntax noprefix\n"

"sub r14, 8\n"

"sub qword ptr [r14], func1-secret\n" // we want to find a way to hide this

"ret\n"

".att_syntax\n"

);

}

int main() {

puts("hello world");

}

Running the above program will give us this result

1

2

3

❯ ./a.out

secret

hello world

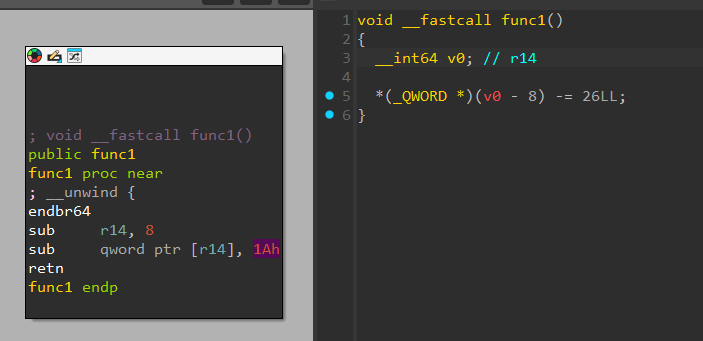

And let’s look at how this looks like in a decompiler!

Although it looks suspicious due to the red font in the decompilation, it is not immediately obvious what this code is doing especially since the logic that executes the secret function is hidden within the library code that is not visible in the decompiler.

By building on top of this small poc, we can create larger programs that will be a pain to reverse due to the difficulty in identifying the program flow.

Bonus - How do we further hide our “malicious” code?

We’ve managed to obfuscate our control flow by continuously modifying the constructor chain pointer and the constructor address within it.

How can we further make our compiled program more discreet and not draw attention to the constructor modifying assembly snippet?

Hide the initial jump in a ‘default’ function

By default, ELF files compiled in GCC contains the frame_dummy function which is executed as a constructor function.

This commonly seen function has become an easily overlooked function by reverse engineers.

As such, if we could fit out callee-saved register modifying piece of assembly code within this function, it would be a perfect hiding place.

To achieve that, I patched the compiled binary to

- Fill up the original

frame_dummywith a bunch of random bytes - Add

jmp register_tm_clonesto the end of my assembly snippet - Patch

SYMTABto set the address offrame_dummyto my assembly snippet

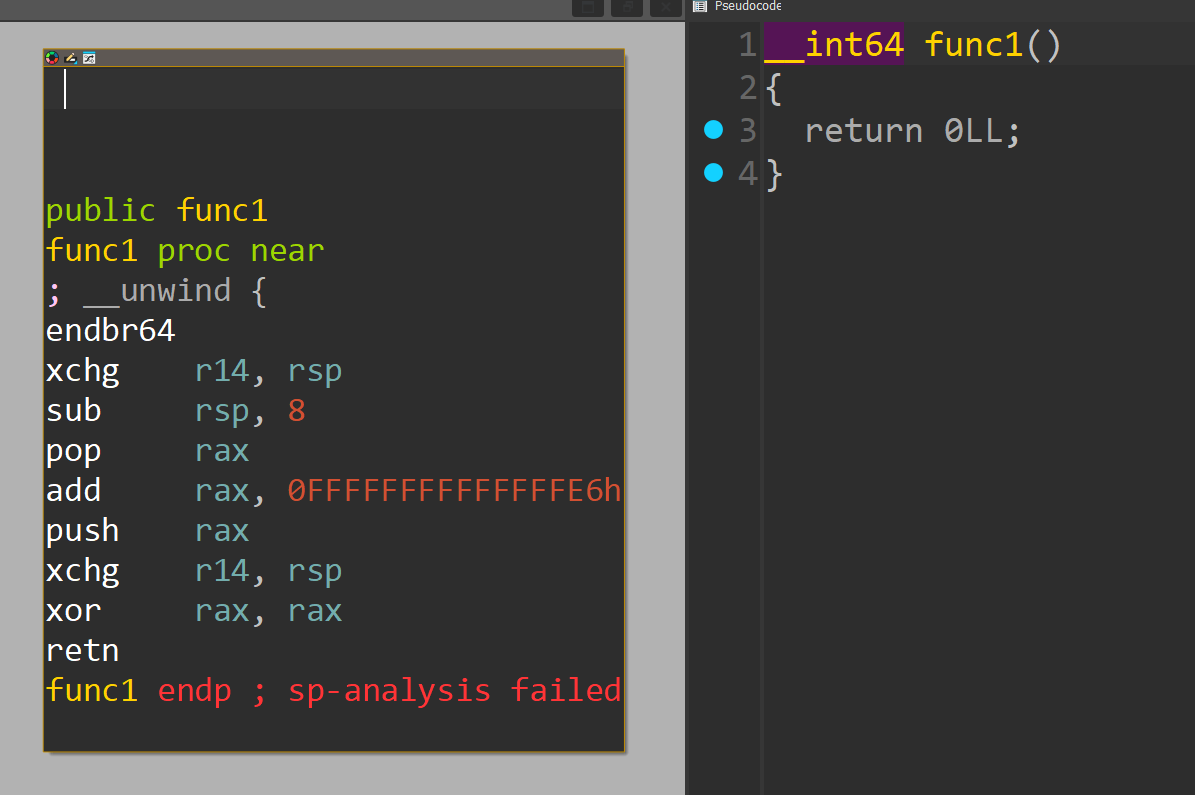

Hide the initial jump from being decompiled

If we were to write a constructor with the following piece of assembly code,

1

2

3

sub r14, 8

add QWORD PTR [r14], 1337

ret

This would be easily recognized and decompiled by tools like IDA to display the following, which might raise suspicion.

1

2

3

4

5

6

void __fastcall func1()

{

__int64 v0; // r14

*(_QWORD *)(v0 - 8) -= 26LL;

}

However, if we messed up the assembly to look weird enough (and still accomplish the same effect), IDA will actually ignore it and not decompile anything! :)

In this specific case, we can use push and pop to effectively do any read/write.

Sick!

Also check out this challenge where I obfuscated a program by replacing all the

movinstructions withpushandpop.That totally broke the decompilation xd

Hide the main shellcode from disassembly

By default, IDA will sweep the bytes in the .text section to try to identify and disassembly any assembly code.

This makes it difficult to discreetly weave in shellcode that we can jump to.

To solve this, we can actually simply add a bunch of random bytes before the shellcode so that IDA will give up on disassembling the entire chunk of bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

# add some junk bytes before

strip_dumb:

.string "\x0e\xe9\x86\xf1/l\xdc\xaa/OZ>\xf9\xbd\xff\x10y\xc6\xf9\xe4"

# make RWX memory so we can decrypt our memory inplace

strip_make_rwx_memory:

lea rsi, [rip]

mov edi, 0xfff

not rdi

and rdi, rsi

lea rbx, [rip+frame_dummy]

xor rdx, rdx

xor rsi, rsi

xor rax, rax

mov si, 0x1000

mov dl, 0x7

mov al, 0xa

syscall

# jmp to next part of shellcode

xchg rsp, r14

sub rsp, 8

pop rax

sub rax, strip_make_rwx_memory-strip_decrypt_memory_init

push rax

xchg rsp, r14

ret

# add some junk bytes after

strip_dump2:

.string "\x9f\xb6LAJVH#T\xc1\x14-\x81v\xcc\xe9\x8dPP\x8a"

Stripping unwanted symbols

When writing my shellcode, I made use of many symbols that would make reversing much more trivial if they are left within the program.

However, I did not want to entirely strip the program as that would remove symbols like main and frame_dummy which would prompt the reverse engineer to manually reverse every function.

As such, I prefixed all my symbols with strip_ and manually parsed the symbol table to remove entries that begin with strip_.

The final script can be found later

Encrypt our shellcode

To further discourage IDA to disassemble our shellcode, I also encrypted most of my shellcode at runtime.

I used a script to encrypt the bytes between the symbols ENCRYPT_BEGIN and ENCRYPT_END and included a decrypting routine at the start of the shellcode.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

lea r8, [rip+ENCRYPT_BEGIN] # begin of encryption area

lea r9, [rip+ENCRYPT_END] # end of encryption area

lea rbx, [rip+frame_dummy] # xor key

# we implement our memory decryption here

strip_decrypt_memory_init:

mov al, byte ptr [rbx]

xor [r8], al

inc rbx

inc r8

xchg rsp, r14

sub rsp, 8

pop rax

cmp r8, r9 # if r8 == r9

jnz strip_l20

add rax, strip_check_flag_init-strip_decrypt_memory_init

strip_l20:

push rax

xchg rsp, r14

ret

The loop is also implemented by deciding using a comparison to decide whether to modify the constructor pointer.

The ugly patching code

Finally, here’s the super super ugly code that I used to patch the ELF to look as “Hello World” as possible :)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from capstone import *

from keystone import *

from pwn import xor

import struct

cs = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

cs.detail = True

ks = Ks(KS_ARCH_X86, KS_MODE_64)

def get_symtab_sh_info_offset(filename):

with open(filename, 'rb') as f:

elf = ELFFile(f)

symtab = elf.get_section_by_name('.symtab')

if symtab is None:

return None, "No .symtab section found"

section_index = elf.get_section_index(symtab.name)

section_header_offset = elf['e_shoff'] + section_index * elf['e_shentsize']

sh_info_offset = section_header_offset + 44

return sh_info_offset

def get_symtab_sh_size_offset(filename):

with open(filename, 'rb') as f:

elf = ELFFile(f)

symtab = elf.get_section_by_name('.symtab')

if symtab is None:

return None, "No .symtab section found"

section_index = elf.get_section_index(symtab.name)

section_header_offset = elf['e_shoff'] + section_index * elf['e_shentsize']

sh_size_offset = section_header_offset + 32

return sh_size_offset

filename = "poc"

with open(filename, 'rb') as f:

elffile = ELFFile(f)

symtab = elffile.get_section_by_name('.symtab')

offset = symtab['sh_offset']

size = symtab['sh_size']

symtab = symtab.data()

strtab = elffile.get_section_by_name('.strtab')

strtab_offset = strtab['sh_offset']

strtab = strtab.data()

symtab = [symtab[i:i+0x18] for i in range(0, len(symtab), 0x18)]

final_symtab = []

strtab_strip = []

# strip symbols that we should strip

# we should also strip strtab names

for entry in symtab:

sym_name_offs = struct.unpack("<I", entry[:4])[0]

if sym_name_offs:

sym_name = ""

i = 0

while True:

if strtab[sym_name_offs+i] == 0:

break

sym_name += chr(strtab[sym_name_offs+i])

i += 1

if sym_name.startswith("strip") or sym_name.startswith(".strip"):

strtab_strip.append((sym_name_offs, i))

continue

final_symtab.append(entry)

# now we also want to remove frame_dummy

frame_dummy_entry = False

for entry in final_symtab:

sym_name_offs = struct.unpack("<I", entry[:4])[0]

if sym_name_offs:

sym_name = ""

i = 0

while True:

if strtab[sym_name_offs+i] == 0:

break

sym_name += chr(strtab[sym_name_offs+i])

i += 1

if sym_name == "frame_dummy" and not frame_dummy_entry:

frame_dummy_entry = entry

frame_dummy_addr = struct.unpack("<Q", entry[8:16])[0]

# strtab_strip.append((sym_name_offs, i))

# break

elif sym_name.endswith("ENCRYPT_BEGIN"):

encrypt_start = entry

encrypt_start_addr = struct.unpack("<Q", entry[8:16])[0]

print(encrypt_start_addr)

elif sym_name.endswith("ENCRYPT_END"):

encrypt_end = entry

encrypt_end_addr = struct.unpack("<Q", entry[8:16])[0]

print(encrypt_end_addr)

final_symtab.remove(frame_dummy_entry)

final_symtab.remove(encrypt_start)

final_symtab.remove(encrypt_end)

# find fake frame_dummy

for entry in final_symtab:

sym_name_offs = struct.unpack("<I", entry[:4])[0]

if sym_name_offs:

sym_name = ""

i = 0

while True:

if strtab[sym_name_offs+i] == 0:

break

sym_name += chr(strtab[sym_name_offs+i])

i += 1

if sym_name == "frame_dummy":

fake_frame_dummy_addr = struct.unpack("<Q", entry[8:16])[0]

new_symtab = b"".join(final_symtab) + b"\x00"*(0x18*(len(symtab)-len(final_symtab)))

assert len(new_symtab) == size

with open(filename, 'rb') as f:

file_contents = bytearray(f.read())

# we create our new strtab

file_contents[offset:offset+size] = new_symtab

# we NULL all the strtab entries that are useless now

# we don't want to give readable strings ;)

for entry in strtab_strip:

file_contents[strtab_offset+entry[0]:strtab_offset+entry[0]+entry[1]] = b"\x00"*entry[1]

# we need to update symtab section size

file_contents[get_symtab_sh_size_offset(filename):get_symtab_sh_size_offset(filename)+8] = struct.pack("<Q", 0x18*(len(final_symtab))) # why do we need to include X blank entries??

# we need to update symtab sh_info to 0

file_contents[get_symtab_sh_info_offset(filename):get_symtab_sh_info_offset(filename)+4] = struct.pack("<I", 0) # why do we need to include X blank entries??

# we null the old constructor frame_dummy

register_tm_clones_addr = next(cs.disasm(file_contents[frame_dummy_addr+4:frame_dummy_addr+9], frame_dummy_addr+4)).op_str

file_contents[frame_dummy_addr:frame_dummy_addr+9] = b"\x00"*9

# we add jmp register_tm_clones back into our fake frame dummy to make it seem legit

replace_offs = file_contents.index(struct.pack(">I", 0xcafebabe))

file_contents[replace_offs:replace_offs+5] = ks.asm(f"jmp {register_tm_clones_addr}", replace_offs)[0]

# we replace the old constructor with the new constructor

file_contents = file_contents.replace(struct.pack("<Q", frame_dummy_addr), struct.pack("<Q", fake_frame_dummy_addr))

# we ENCRYPT the code between ENCRYPT_START and ENCRYPT_END

# ENCRYPT ^ frame_dummy

file_contents[encrypt_start_addr:encrypt_end_addr] = xor(file_contents[encrypt_start_addr:encrypt_end_addr], file_contents[fake_frame_dummy_addr:fake_frame_dummy_addr+encrypt_end_addr-encrypt_start_addr])

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

f.write(file_contents)

Conclusion

By utilizing callee-saved registers from library functions, we were able to create an invisible jump that executes some shellcode discreetly.

While this is not any ground-breaking research, such research is fun and interesting as it gives us insights into how compilers and our reverse-engineering tools work and might even be useful by helping us understand and prepare for more complicated low-level assembly tricks that might be used in malware to achieve code obfuscation.

In my next obfuscation adventure, I hope to be able to do less manual work and directly instrument the assembly code on the compiler level, possibly through writing LLVM passes.

Hopefully this was a good read and see you in the next one!