A deep dive into modern Windows Structured Exception Handler (SEH) ⚠️

On Windows, the operating system implements its own unique exception handling mechanisms — Structured Exception Handling (SEH) and Vectored Exception Handling (VEH) — which is an extension on top of the conventional C/C++ language to provide support for runtime error handling.

These are only available for windows executables since it relies on the windows kernel to catch the exception and transfer the control flow back to the program!

These unique methods of exception handling makes it complicated for us to reverse engineer and trace the control flow of the program without sufficient understanding of how the handlers are installed and implemented.

In this post, we will take a dive into the low-level internals to understand how these exception handlers are implemented.

x64 Structured Exception Handling

SEH implementation varies greatly between 32-bit and 64-bit programs.

Most of this blog post will study how SEH handlers work for 64-bit programs, after which, we will briefly compare it with the corresponding 32-bit implementation as well as VEH.

In order to better understand how an SEH handlers would look like in a compiled program, we can compile a simple program of our own and look at it in IDA. The following compiled program can be downloaded here.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

__try {

printf("__try block\n");

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

printf("__except block\n");

}

return 0;

}

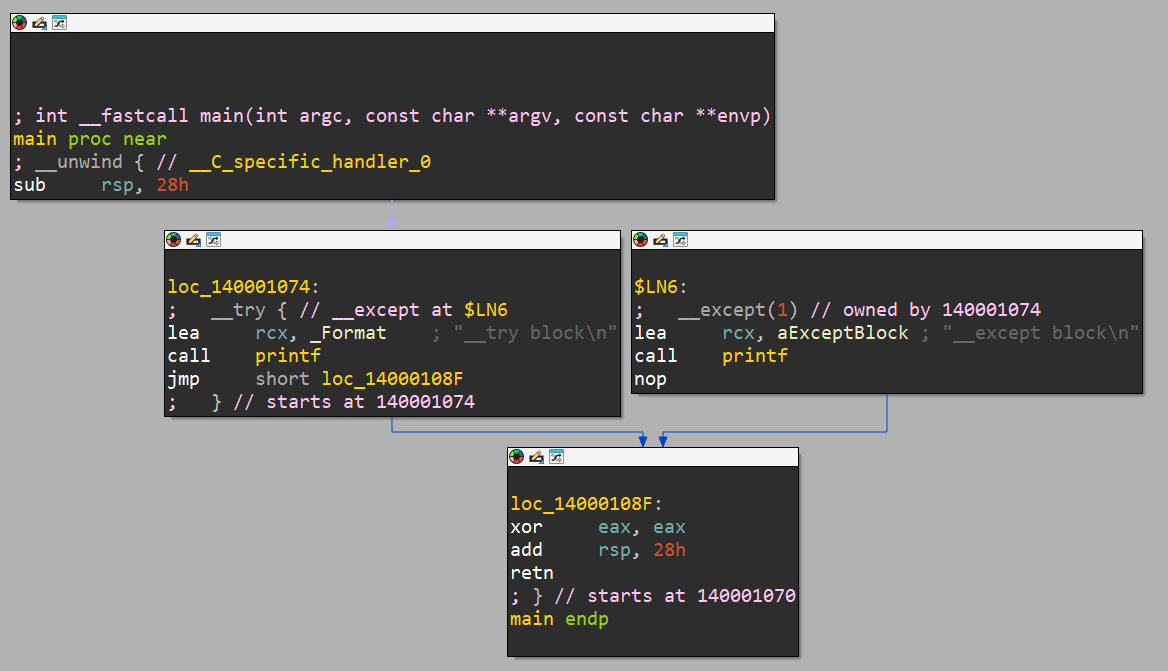

Let’s look at how this program disassembly would look like in IDA!

As you can see, we can identify our try and except blocks. However, the control flow does not seem to ever branch to the except block. How does the program know where the exception handler is located then?

In the next section, we will try to inspect deeper to see how the program keeps track of such exception handlers.

Where to find x64 exception handler?

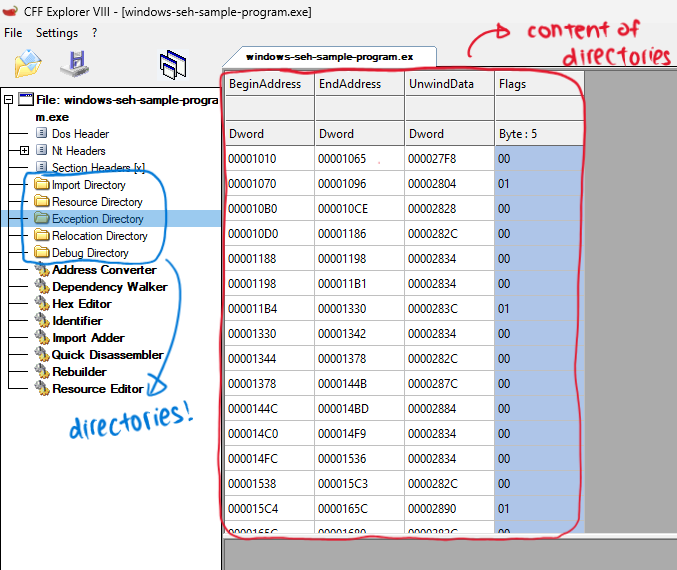

Within a PE image, there are various directories that contain information about the image. For example, if the image has any exports, there will be an export directory that describes the exports.

In the case of an x64 image, there happens to be an Exception Directory which we can see with the use of tools such as CFF Explorer.

exception directory entries in sample exe

exception directory entries in sample exe

As you can see, the exception directory contains many RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries which is defined as such:

1

2

3

4

5

typedef struct _RUNTIME_FUNCTION {

ULONG BeginAddress;

ULONG EndAddress;

ULONG UnwindData;

} RUNTIME_FUNCTION, *PRUNTIME_FUNCTION;

We can naively interpret this as follows:

Each

RUNTIME_FUNCTIONentry defines a set of instructions within theUnwindDatafield that tells it how to handle any exception that occurs between theBeginAddressandEndAddressaddress of the program.

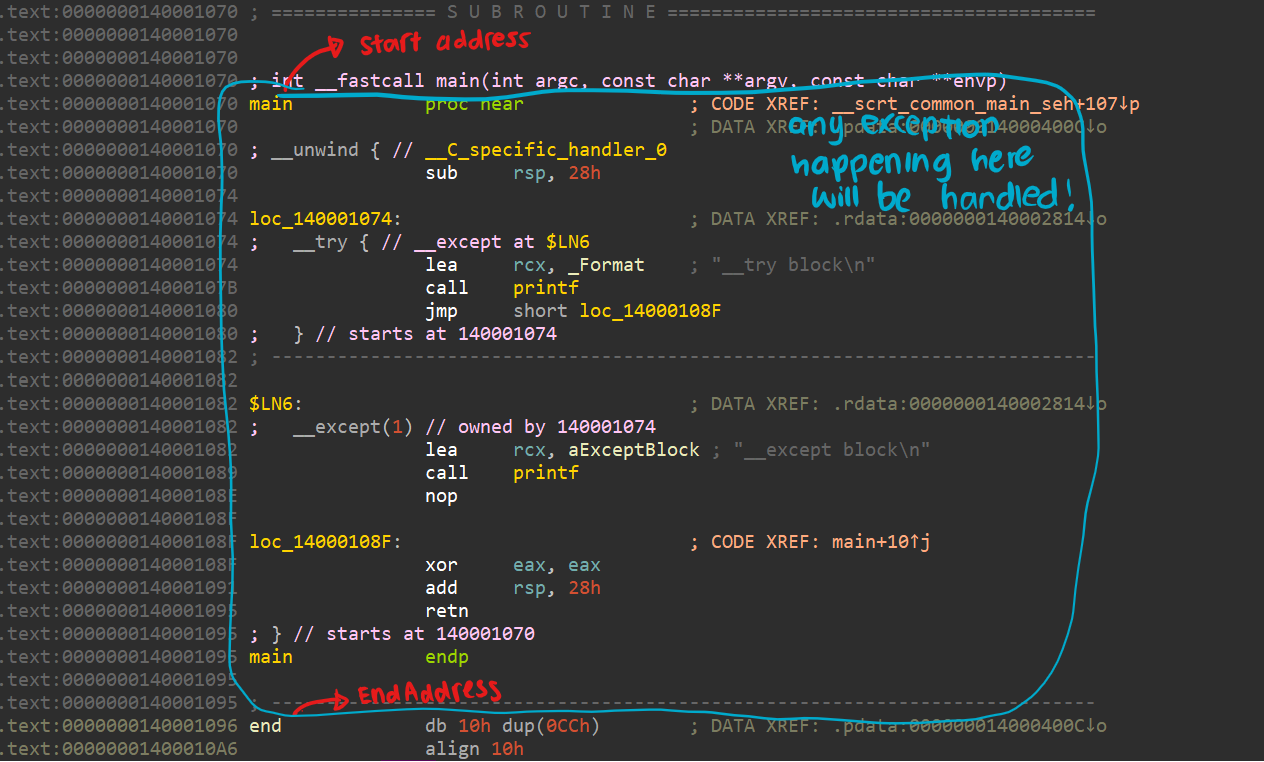

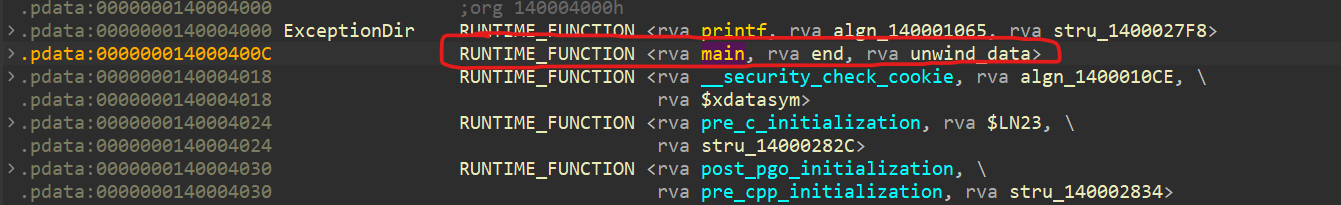

In order to take a deeper dive at the contents of the exception directory, we can inspect it in IDA by using the g hotkey and jumping to ExceptionDir. From there, we can see the main function entry right off the bat!

exception directory entry for the main function

exception directory entry for the main function

In this case, we can see the corresponding fields of the RUNTIME_FUNCTION struct and how it actually corresponds with the actual try except block!

1

2

3

4

5

struct _RUNTIME_FUNCTION {

ULONG BeginAddress = main;

ULONG EndAddress = end;

ULONG UnwindData = unwind_data;

};

We can even see how this exception is handled by looking into the UNWIND_INFO struct pointed to by unwind_data.

As you can see, the unwind data does indeed contain a pointer to the exception handler which is called when an exception is raised! However, what are the other fields in the UNWIND_INFO and what do they even do?

Looking at implementation of exception handler in NTDLL

So far we have very briefly covered how SEH exceptions are handled in 64-bit programs. However, there’s actually much more that happens than it seems. In order to look at this, we will have to start to look at the exception handling source code.

I started off my analysis in this part by reverse engineering ntdll.dll in IDA. 😅

However for the sake of our sanity, we will refer to code snippets from ReactOS which is an open-source implementation of Windows whenever possible and will refer back to ntdll when ReactOS is insufficient.

As soon as an exception is raised (for both VEH and SEH), the kernel would catch the exception and pass the control flow to the ntdll!KiUserExceptionDispatcher function which would find the appropriate exception handler to handle the exception.

Here’s a function trace of some of the more important functions that are called from the exception dispatcher.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

KiUserExceptionDispatcher // Windows Kernel Internal (KI) API

-> RtlDispatchException // main logic for exception handling

-> RtlpCallVectoredHandlers // call any VEH

-> RtlLookupFunctionEntry // look for valid PRUNTIME_FUNCTION entry in ExceptionDirectory

-> RtlpLookupDynamicFunctionEntry // if no valid PRUNTIME_FUNCTION, run any dynamic callbacks

-> RtlVirtualUnwind / RtlpxVirtualUnwind // perform stack frame unwinding

-> RtlpExecuteHandlerForException // execute exception handler!

We will explain RtlLookupFunctionEntry and RtlpxVirtualUnwind in detail.

ContextRecord

One of the important data structure that is passed from KiUserExceptionDispatcher to RtlDispatchException when an exception occurs is the CONTEXT struct.

This struct contains information about the state of the registers at the point of the exception being raised.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

typedef struct _CONTEXT {

DWORD64 P1Home;

DWORD64 P2Home;

DWORD64 P3Home;

DWORD64 P4Home;

DWORD64 P5Home;

DWORD64 P6Home;

DWORD ContextFlags;

DWORD MxCsr;

WORD SegCs;

WORD SegDs;

WORD SegEs;

WORD SegFs;

WORD SegGs;

WORD SegSs;

DWORD EFlags;

DWORD64 Dr0;

DWORD64 Dr1;

DWORD64 Dr2;

DWORD64 Dr3;

DWORD64 Dr6;

DWORD64 Dr7;

DWORD64 Rax;

DWORD64 Rcx;

DWORD64 Rdx;

DWORD64 Rbx;

DWORD64 Rsp;

DWORD64 Rbp;

DWORD64 Rsi;

DWORD64 Rdi;

DWORD64 R8;

DWORD64 R9;

DWORD64 R10;

DWORD64 R11;

DWORD64 R12;

DWORD64 R13;

DWORD64 R14;

DWORD64 R15;

DWORD64 Rip;

union {

XMM_SAVE_AREA32 FltSave;

NEON128 Q[16];

ULONGLONG D[32];

struct {

M128A Header[2];

M128A Legacy[8];

M128A Xmm0;

M128A Xmm1;

M128A Xmm2;

M128A Xmm3;

M128A Xmm4;

M128A Xmm5;

M128A Xmm6;

M128A Xmm7;

M128A Xmm8;

M128A Xmm9;

M128A Xmm10;

M128A Xmm11;

M128A Xmm12;

M128A Xmm13;

M128A Xmm14;

M128A Xmm15;

} DUMMYSTRUCTNAME;

DWORD S[32];

} DUMMYUNIONNAME;

M128A VectorRegister[26];

DWORD64 VectorControl;

DWORD64 DebugControl;

DWORD64 LastBranchToRip;

DWORD64 LastBranchFromRip;

DWORD64 LastExceptionToRip;

DWORD64 LastExceptionFromRip;

} CONTEXT, *PCONTEXT;

For example, Context->Rip would hold an instruction pointer to the instruction that resulted in the exception.

We will see plenty of this, so we can keep this in mind later.

RtlLookupFunctionEntry

This function iterates through the RUNTIME_FUNCTION data structures in the Exception Directory and look for an entry such that BeginAddress < Context->Rip < EndAddress.

If it doesn’t find a valid entry, it would call RtlpLookupDynamicFunctionEntry to look for dynamic function entries. Wait, what’s that?

RtlpLookupDynamicFunctionEntry

Previously, we’ve mentioned that RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries are found in ExceptionDir which is embedded into an executable at compile time.

However as a way to support dynamically-generated or just-in-time compiled code, there are 2 WinAPIs that can be used to add more RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries beyond the ExceptionDir

Note that this is only invoked IF AND ONLY IF a valid

RUNTIME_FUNCTIONcannot already be found in theExceptionDirof the executable image.

The first way is using RtlInstallFunctionTableCallback which takes in a callback function as a parameter.

This callback function will be called and is expected to return a RUNTIME_FUNCTION struct.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

BOOLEAN RtlInstallFunctionTableCallback(

DWORD64 TableIdentifier, // Must have lowest 3 bits set to 0x3

DWORD64 BaseAddress, // Base address of the code

DWORD Length, // Length of the code region

PGET_RUNTIME_FUNCTION_CALLBACK Callback, // Your callback function

PVOID Context, // Optional context passed to callback

PCWSTR OutOfProcessCallbackDll // Usually NULL for in-process

);

The second way is using RtlAddFunctionTable/RtlAddGrowableFunctionTable. Unlike the previous API, you have to provide RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries upfront which will be added to an array of RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries that will be looked up when an exception occurs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

NTSTATUS RtlAddGrowableFunctionTable(

PVOID *DynamicTable, // Out parameter - receives table handle

PRUNTIME_FUNCTION FunctionTable, // Initial array of RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries

DWORD EntryCount, // Current number of entries

DWORD MaximumEntryCount, // Maximum entries the table can grow to

ULONG_PTR RangeBase, // Base address of code range

ULONG_PTR RangeEnd // End address of code range

);

Cool! The flexibility to install RUNTIME_FUNCTION entries on the go (especially by calling a function of our own) could make reverse engineering a whole lot more complicated :)

RtlVirtualUnwind

Exceptions can happen in the middle of an extremely complicated function where the stack and registers are in a mess. In order for us to hand the execution back to the exception handler, we will have to recover the state of the stack.

Stack unwinding ensures that even when exceptions occur, your program maintains proper cleanup and resource management by systematically walking back through function frames, executing cleanup handlers, and restoring program state - maintaining program integrity even during error conditions.

Earlier, we mentioned briefly about UnwindData and UNWIND_INFO. The UnwindData in RUNTIME_FUNCTION contains the offset in the program to the UNWIND_INFO data structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

typedef union _UNWIND_CODE

{

struct

{

UBYTE CodeOffset;

UBYTE UnwindOp:4;

UBYTE OpInfo:4;

};

USHORT FrameOffset;

} UNWIND_CODE, *PUNWIND_CODE;

typedef struct _UNWIND_INFO

{

UBYTE Version:3;

UBYTE Flags:5;

UBYTE SizeOfProlog;

UBYTE CountOfCodes;

UBYTE FrameRegister:4;

UBYTE FrameOffset:4;

UNWIND_CODE UnwindCode[1];

/* union {

OPTIONAL ULONG ExceptionHandler;

OPTIONAL ULONG FunctionEntry;

};

OPTIONAL ULONG ExceptionData[];

*/

} UNWIND_INFO, *PUNWIND_INFO;

Essentially, the UNWIND_INFO contains an array of UNWIND_CODEs that defines a set of instructions to be executed in order to unwind/recover the state of the stack and registers for a given function before passing the execution back to the ExceptionHandler.

The set of Unwind Opcodes are nicely documented here or you can also find the corresponding code for it here.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

/* Process the remaining unwind ops */

while (i < UnwindInfo->CountOfCodes)

{

UnwindCode = UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i];

switch (UnwindCode.UnwindOp)

{

case UWOP_PUSH_NONVOL:

Reg = UnwindCode.OpInfo;

PopReg(Context, ContextPointers, Reg);

i++;

break;

case UWOP_ALLOC_LARGE:

if (UnwindCode.OpInfo)

{

Offset = *(ULONG*)(&UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i+1]);

Context->Rsp += Offset;

i += 3;

}

else

{

Offset = UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i+1].FrameOffset;

Context->Rsp += Offset * 8;

i += 2;

}

break;

case UWOP_ALLOC_SMALL:

Context->Rsp += (UnwindCode.OpInfo + 1) * 8;

i++;

break;

case UWOP_SET_FPREG:

Reg = UnwindInfo->FrameRegister;

Context->Rsp = GetReg(Context, Reg) - UnwindInfo->FrameOffset * 16;

i++;

break;

case UWOP_SAVE_NONVOL:

Reg = UnwindCode.OpInfo;

Offset = UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i + 1].FrameOffset;

SetRegFromStackValue(Context, ContextPointers, Reg, (DWORD64*)Context->Rsp + Offset);

i += 2;

break;

case UWOP_SAVE_NONVOL_FAR:

Reg = UnwindCode.OpInfo;

Offset = *(ULONG*)(&UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i + 1]);

SetRegFromStackValue(Context, ContextPointers, Reg, (DWORD64*)Context->Rsp + Offset);

i += 3;

break;

case UWOP_EPILOG:

i += 1;

break;

case UWOP_SPARE_CODE:

ASSERT(FALSE);

i += 2;

break;

case UWOP_SAVE_XMM128:

Reg = UnwindCode.OpInfo;

Offset = UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i + 1].FrameOffset;

SetXmmRegFromStackValue(Context, ContextPointers, Reg, (M128A*)Context->Rsp + Offset);

i += 2;

break;

case UWOP_SAVE_XMM128_FAR:

Reg = UnwindCode.OpInfo;

Offset = *(ULONG*)(&UnwindInfo->UnwindCode[i + 1]);

SetXmmRegFromStackValue(Context, ContextPointers, Reg, (M128A*)Context->Rsp + Offset);

i += 3;

break;

case UWOP_PUSH_MACHFRAME:

/* OpInfo is 1, when an error code was pushed, otherwise 0. */

Context->Rsp += UnwindCode.OpInfo * sizeof(DWORD64);

/* Now pop the MACHINE_FRAME (RIP/RSP only. And yes, "magic numbers", deal with it) */

Context->Rip = *(PDWORD64)(Context->Rsp + 0x00);

Context->Rsp = *(PDWORD64)(Context->Rsp + 0x18);

ASSERT((i + 1) == UnwindInfo->CountOfCodes);

goto Exit;

}

}

After all the UNWIND_CODEs have been ‘executed’, the exception dispatcher will finally return the execution of the program back to the ExceptionHandler

That is most of the relevant details of the x64 Structured Exception Handling implementation.

Compared to 32-bit SEH…

As you have seen, 64-bit SEH handlers are almost always (by default) stored in a read-only Exception Directory that is compiled into the program.

On the contrary, 32-bit SEH handlers are stored in a linked list of exception handlers on the stack at runtime. Each function that uses SEH would have to run a snippet of assembly as shown below to install the handler.

1

2

3

push DWORD PTR fs:[0] # Save current handler

push <exception_handler> # Push address of new handler

mov DWORD PTR fs:[0], esp # Point SEH chain to new record

When an exception occurs, the system walks this chain from newest to oldest until a handler processes the exception. Each function must unlink its handlers before returning.

SEH vs VEH

While both SEH and VEH has the same idea of handling exceptions, the implementation varies greatly.

Vectored Exception Handler

The most important thing to note about VEH is that it monitors for exception process-wide and it is registered by calling the AddVectoredExceptionHandler function at runtime.

Here’s an example of how VEH can be used in a program.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

// generated by https://claude.ai/

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

LONG WINAPI VectoredHandler(PEXCEPTION_POINTERS pExceptionInfo)

{

// Check if it's an access violation

if (pExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionCode == EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION)

{

printf("Access Violation Detected!\n");

printf("Violation Address: 0x%p\n", pExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress);

printf("Memory Address: 0x%p\n", (void*)pExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionInformation[1]);

// Return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH to let other handlers process it

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH;

}

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

int main()

{

// Install our VEH - the second parameter as TRUE means it's added to the front of VEH chain

PVOID handler = AddVectoredExceptionHandler(1, VectoredHandler);

// Trigger an access violation

int* p = NULL;

*p = 42; // This will cause an access violation

// We won't reach this due to the crash

RemoveVectoredExceptionHandler(handler);

return 0;

}

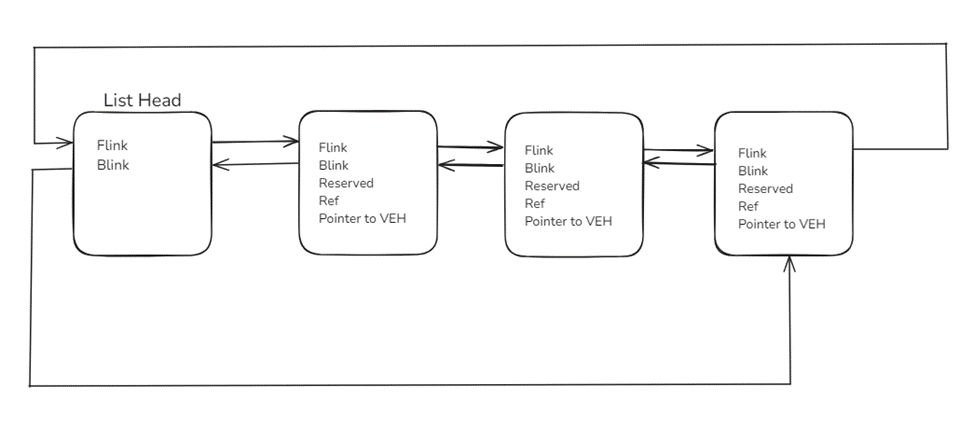

When a VEH handler is registered, it is added to the back of the exception chain.

When an exception is raised, it starts from the list head and walks through each item looking for an appropriate handler. If it does not find an appropriate handler, the process will be terminated.

Conclusion

This short blog post was inspired by Flare-On 11’s Level 9 challenge, Serpentine , which made use of x64 SEH dynamic table entries and unwind codes to obfuscate control flow and hide instructions.

This blog post is not conclusive and most definitely does not cover ALL the intricacies of the exception handling process in Windows. If there are any inaccuracies shared, please reach out to me via email!

Further Reading

These are some interesting blog posts to learn more about the internals of windows exception handling as well as how we can manipulate it to evade antivirus/edr and deter reverse engineering efforts.