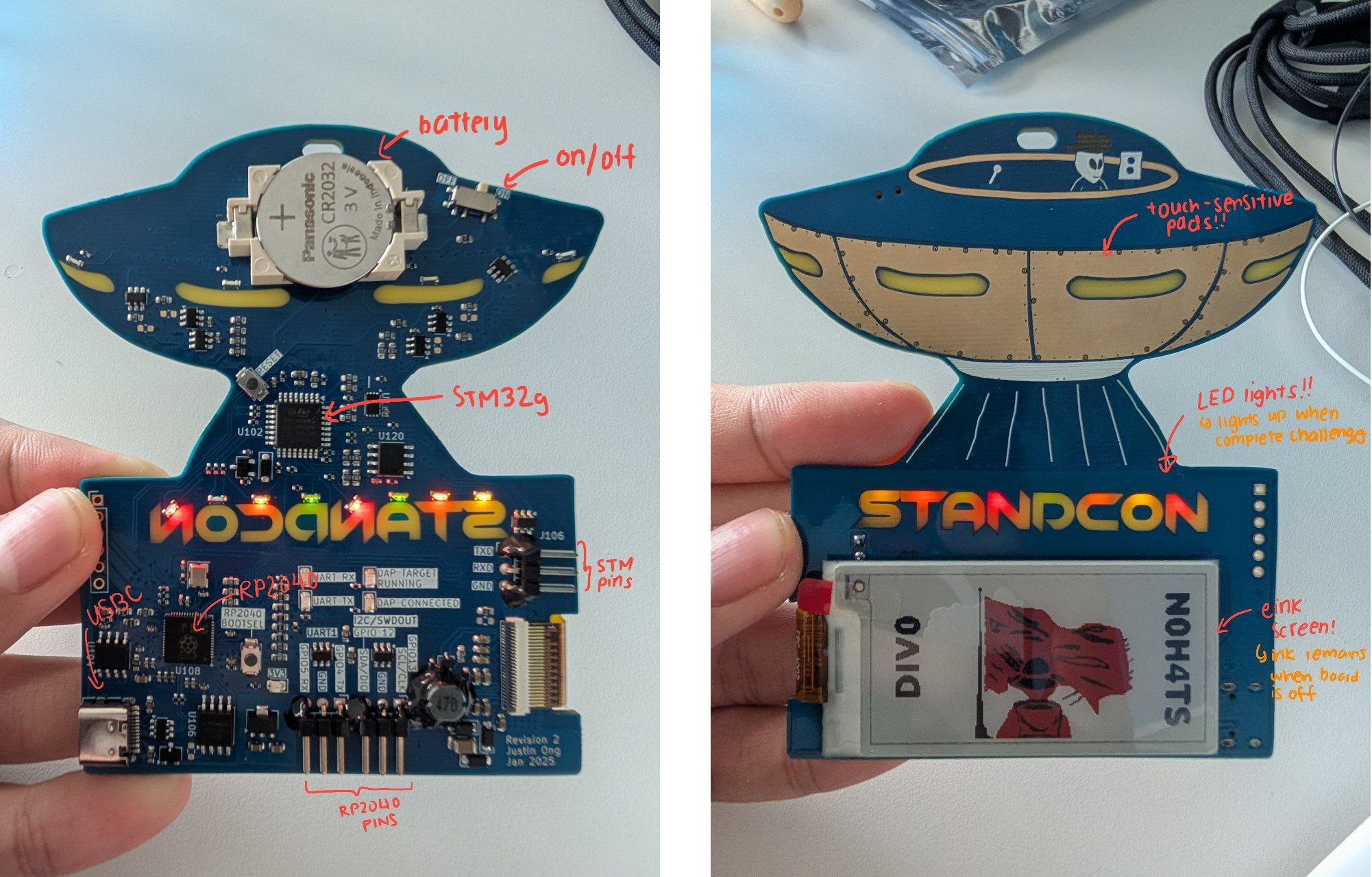

STANDCON Conference 2025 Hardware Badge

9 months after my last hardware venture playing around with the Off-By-One Conference Badge, I once again find myself intrigued with yet another conference badge.

Although I was initially hesitant to purchase the hardware badge, upon hearing that it was made by the legend Justin with some challenges by mcdulltii, I immediately made the purchase and I have no regrets.

This board contains two microprocessors, the RP2040 (running micropython) and STM32.

There are a total of 8 challenges, whereby each letter will light up after a challenge has been completed.

The sample code as well as the challenges for this badge has been open sourced here.

Micropython Challenges

This section contains the writeup to the challenges that are solved solely within the RP2040 micropython console.

Baby Crackme

We can connect to the RP2040 Micropython REPL via mpremote and import the challenge using import chall_crackme.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

from machine import Pin

import rp2

"""

For input() to be handled correctly when ran with mpremote, this file must be called from repl ie

mpremote repl

> import chall_crackme

"""

@rp2.asm_pio(out_shiftdir=rp2.PIO.SHIFT_RIGHT)

def beepbop():

pull()

out(y, 3)

in_(y, 3)

out(x, 5)

pull()

in_(osr, 2)

in_(x, 5)

out(null, 2)

in_(osr, 6)

push()

sm = rp2.StateMachine(0, beepbop)

sm.active(1)

flag = input("Enter flag: ")

if len(flag) % 2 == 1:

flag += chr(0xA5)

out = []

for c in flag:

sm.put(ord(c))

if sm.rx_fifo():

out.append(sm.get())

if out == [

49947,

15129,

31708,

51800,

31564,

31639,

4507,

58077,

6732,

58076,

35416,

51801,

44009,

]:

print("Correct!")

else:

print(":(")

Every 2 characters that you input, it will output a seemingly random number. We can brute-force the flag 2 characters at a time to obtain the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

charset = r"0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ!\"#$%&\'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\\]^_`{|}~"

known = ""

def brute_next_2_chars(known):

for i in range(len(charset)):

for j in range(len(charset)):

sm = rp2.StateMachine(0, beepbop)

sm.active(1)

out = []

t = known + charset[i] + charset[j]

for c in t:

sm.put(ord(c))

if sm.rx_fifo():

out.append(sm.get())

if out == ans[:len(t)//2]:

print(t)

return t

while True:

known = brute_next_2_chars(known)

# output

"""

fl

flag

flag{s

flag{sNa

flag{sNak3

flag{sNak3s_

flag{sNak3s_0n

flag{sNak3s_0n_t

flag{sNak3s_0n_tH3

flag{sNak3s_0n_tH3_p

flag{sNak3s_0n_tH3_pLa

flag{sNak3s_0n_tH3_pLaNe

"""

flag: flag{sNak3s_0n_tH3_pLaNe}

I spy with my little eye

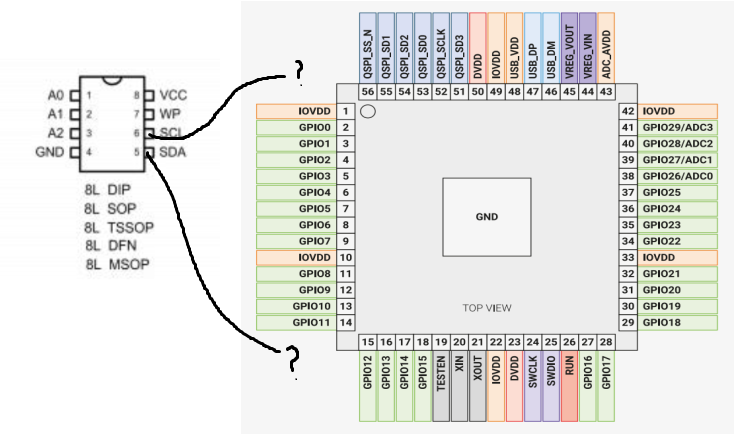

… a flag stored in the EEPROM (U104) connected to the RP2040.

With some research, I found out that we can access the EEPROM using the I2C protocol.

In order to communicate over the I2C protocol, we will need to connect the following components

- SDA (Serial Data)

- Transmits the data

- SCL (Clock Signal)

- Used to sync the data transmission

In order to know which pins of the RP2040 is connected to the SDA and SCL of the EEPROM, we can trace the wiring following the datasheet.

datasheet helps us to identify the pin significance

datasheet helps us to identify the pin significance

As we can see, SDA is connected to GPIO20 and SCL is connected to GPIO17.

Subsequently, we can follow the I2C protocol to read the flag from address 0 of the EEPROM.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

from machine import I2C, Pin

i2c = I2C(0, sda=Pin(20), scl=Pin(17), freq=100000)

# as part of the i2c protocol, we first tell the I2C the address that we want to read from

i2c.writeto(80, bytearray([0])) # address 0

# subsequently, we can read 100 bytes from the specified address

print(i2c.readfrom(80, 100))

# Output: b'flag{ey3_0n_th3_pr1zE}\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff'

Simon Says

For this challenge, there was some source code given to us but I chose to ignore it and reverse-engineer the more interesting looking game.mpy file.

We can use mpy-tool to disassemble micropython bytecode

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

> python .\micropython\tools\mpy-tool.py -d ./game.mpy

mpy_source_file: ./game.mpy

source_file: build/game.native.mpy

header: 4d:06:13:1f

qstr_table[4]:

build/game.native.mpy

e

l

v

obj_table: []

simple_name: build/game.native.mpy

raw data: 1664 c8:e2:00:00:f7:b5:15:4b:01:92:15:4a:7b:44:9d:58:0e:00:2b:00:e0:33:1b:68:04:00:98:47:00:21:eb:6c ...

However, we did not manage to obtain any bytecode but instead got some native code. This means that the .mpy was probably compiled into assembly code from C.

By throwing it into a decompile and specifying 32-bit ARM-LE, we can scroll around and quickly find this interesting looking piece of code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

v67[1] = v42; // v42 is some unknown 1-byte integer

v67[0] = v59; // v59 is some unknown 1-byte integer

v67[2] = v58; // v58 is some unknown 1-byte integer

sub_1E8((int)byte_664, &v66);

v59 = v66;

for ( i = 0; i != v59; ++i )

{

for ( j = i; j > 2; j -= 3 )

;

v55 = v67[j];

v56 = 85;

if ( (i & 1) == 0 )

v56 = -86;

*((_BYTE *)v60 + i) = (v55 << (i + 1 - 8 * (i >> 3))) ^ ((v56 ^ enc_flag[i]) - (v55 >> (i & 3)));

}

We can throw the above code to ChatGPT to get it to generate the python equivalent and write a brute-force script to decrypt the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

def decrypt(v67):

enc_flag = bytes.fromhex("C6C85F9FFCA4902883110547E5E9DE3AD76F438E9B55153AB4CA799024BA9C2C83770000")

v59 = len(enc_flag) # Assuming v59 corresponds to the length of enc_flag

flag = [0] * v59 # Result array, which will store the transformed bytes

# Emulating the loop in Python

for i in range(v59):

j = i

while j > 2:

j -= 3 # Same behavior as `for (j = i; j > 2; j -= 3)`

v55 = v67[j] # v67[j] corresponds to accessing v67 array

v56 = 85

if i % 2 == 0: # Check if `i` is even

v56 = -86

# Performing the bitwise operations as per the original C code

enc_flag_val = enc_flag[i]

flag[i] = (v55 << (i + 1 - 8 * (i >> 3))) ^ ((v56 ^ enc_flag_val) - (v55 >> (i & 3)))

flag = [chr(i & 0xff) for i in flag]

return flag

v67 = [0, 0, 0]

known = "flag"

for i in range(3):

for j in range(256):

v67[i] = j

if decrypt(v67)[i] == known[i]:

break

print(''.join(decrypt(v67)))

# Output: flag{h4v3_y0u_pl4y3d_s1m0n_b3f0r3}

Hardware/STM-related Challenges

Finally, we get to get our hands dirty by touching the hardware challenges.

This section is significantly more interesting as we start using our RP2040 as a tool to interact with the STM32 microcontroller.

Firmware Dump

1

2

3

$ .\picotool.exe save -a out.bin

$ strings out.bin | grep 'flag{'

flag{d0nt_l00k_a7_mY_1nsid3s}

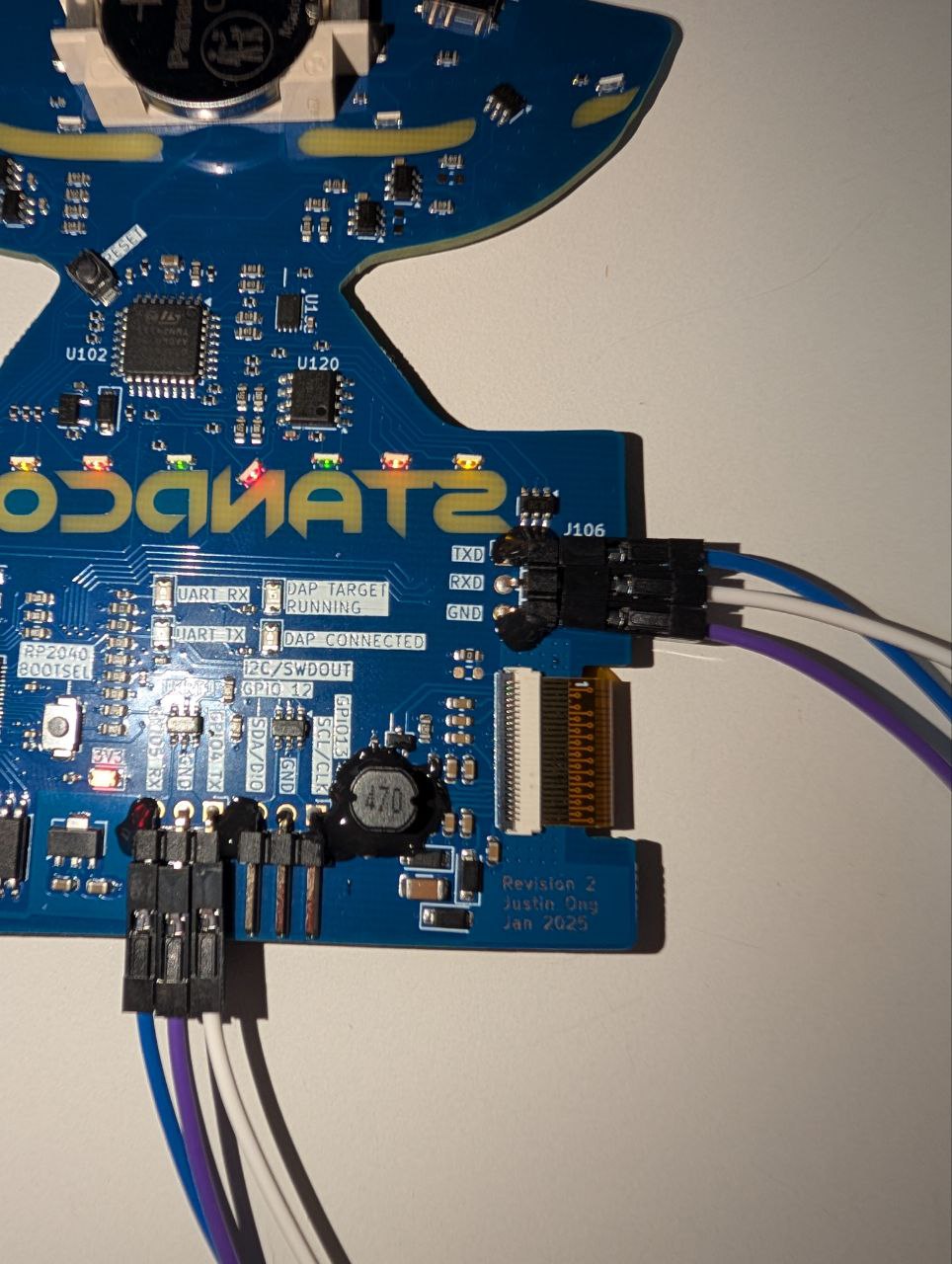

Connecting

Beep boop. There are two microcontrollers on the board, one directly accessible to the user over USB. Find a way to connect to the target and speak to its console.

We can utilize the exposed UART pins that have been provided for us to connect from the RP2040 to the STM32.

- RX (rp2040) to TX (stm)

- TX (stm) to RX (rp2040)

- GND (rp2040) to GND (stm)

Subsequently, we can use the following template code to interact with the RP2040

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

import sys

import select

from machine import Pin, UART

# This script must be executed from the REPL

# ie with mpremote, `mpremote mount .` then `import uart_tgt`

uart = UART(1, baudrate=9600, tx=Pin(4), rx=Pin(5))

while True:

if uart.any():

c = uart.read(1)

sys.stdout.buffer.write(c)

if select.select([sys.stdin], [], [], 0.0)[0]:

data = sys.stdin.buffer.read(1)

uart.write(data)

However, we have to find the appropriate baud rate in order to be able to exchange data with the STM32.

We can try to brute-force some common baud rates

1

common_baud_rates = [4800, 9600, 19200, 38400, 57600, 115200, 230400, 460800, 921600]

I was unsuccessful with my brute-force attempts. After speaking to the author, I realized that sending data on the some of the wrong baud rates caused the UART to be unresponsive subsequently to all data sent.

The only way to fix this was to hit the RST button between each attempt.

Eventually, we managed to find the correct baud rate of 57600.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

commands:

- flag

- login <password [a-zA-Z0-9_]+>

- pour

- validate

> flag

flag{d1d_y0u_sWap_ur_tx_rx_l1n3s}

Logging In

For this challenge, we have to login with some password.

We can try to write a short script to brute-force a single character.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

import time

from machine import Pin, UART

charset = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ1234567890_"

for i in charset:

uart = UART(1, baudrate=57600, tx=Pin(4), rx=Pin(5))

uart.write(f"login {i}\n")

time.sleep(0.015)

print(uart.read(uart.any()))

# b'login a\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login b\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login c\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login d\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login e\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login f\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login g\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login h\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login i\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login j\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login k\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login l\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login m\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login n\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login o\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login p\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login q\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login r\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login s\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login t\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login u\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login v\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login w\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login x\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login y\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login z\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login A\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login B\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login C\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login D\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login E\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login F\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login G\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login H\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login I\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login J\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login K\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login L\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login M\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login N\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login O\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login P\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login Q\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login R\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login S\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login T\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login U\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login V\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login W\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login X\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login Y\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login Z\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 1\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 2\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 3\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 4\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 5\r\nwrong password'

# b'login 6\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 7\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 8\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 9\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login 0\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

# b'login _\r\nwrong password\r\n> '

As we can see, when trying to use 5 as the first character of the password, the response is incomplete which allows us to infer that it took longer to verify the password.

This implies that the program checks our password character by character, allowing us to do a side-channel attack to brute-force each character and find the input that results in the slowest response.

By continuously modifying the sleep timeout for each additional character found, we can eventually find the password to be 5eSaM3_bR0nz3_Ly0N.

1

2

> login 5eSaM3_bR0nz3_Ly0N

correct! flag{l00k_2_7h3_s1d3}

sudo flag

For this challenge, we have to interact with the following program and pass all the checks

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

#include "Challenge_Perms.hpp"

#include "flags.h"

#include "main.h"

#include <cstdint>

#include <cstring>

extern I2C_HandleTypeDef hi2c2;

constexpr int I2C_TIMEOUT = 100;

constexpr uint8_t EEPROM_ADDRESS = 0xA0;

typedef struct __attribute__((packed)) {

uint16_t user_id;

uint8_t permissions;

uint8_t checksum;

} user_data_t;

bool challenge_perms_run(char *ret) {

uint8_t data_tx[1] = {0};

if (HAL_I2C_Master_Transmit(&hi2c2, EEPROM_ADDRESS, data_tx, 1,

I2C_TIMEOUT) != HAL_OK) {

strcat(ret, "BEEP: internal error: write failed\r\n");

return false;

}

user_data_t data = {0};

if (HAL_I2C_Master_Receive(&hi2c2, EEPROM_ADDRESS | 0x01, (uint8_t *)&data,

sizeof(data), I2C_TIMEOUT) != HAL_OK) {

strcat(ret, "BEEP: internal error: read failed\r\n");

return false;

}

uint8_t *p = (uint8_t *)&data;

uint8_t expected_checksum = 0xB3;

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < sizeof(user_data_t) - 1; i++) {

expected_checksum ^= (*p++);

}

if (data.checksum != expected_checksum) {

strcat(ret, "How puzzling! We appear to have some data corruption...\r\n");

return false;

}

if (data.user_id != 42) {

strcat(ret, "User is...not the answer to life.\r\n");

return false;

}

if (data.permissions < 200) {

strcat(ret, "You do not have enough authorization. This incident will be "

"reported.\r\n");

return false;

}

strcat(ret, "congrats: " FLAG_CHALLENGE_PERMS);

strcat(ret, "\r\n");

return true;

}

Essentially, the data structure stored in the EEPROM of the STM32 is used to determine whether the flag will be printed.

1

2

3

4

5

typedef struct __attribute__((packed)) {

uint16_t user_id; // has to be 42

uint8_t permissions; // has to be > 200

uint8_t checksum; // 0xb3 xor with the previous 3 bytes of the structure

} user_data_t;

We can easily find a valid data structure that would fulfill the above conditions

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

buf = [

42, 0, # user id (2-byte LE)

255, # permission

0xb3 ^ 42 ^ 0 ^ 255 # checksum

]

print(buf)

# [42, 0, 255, 102]

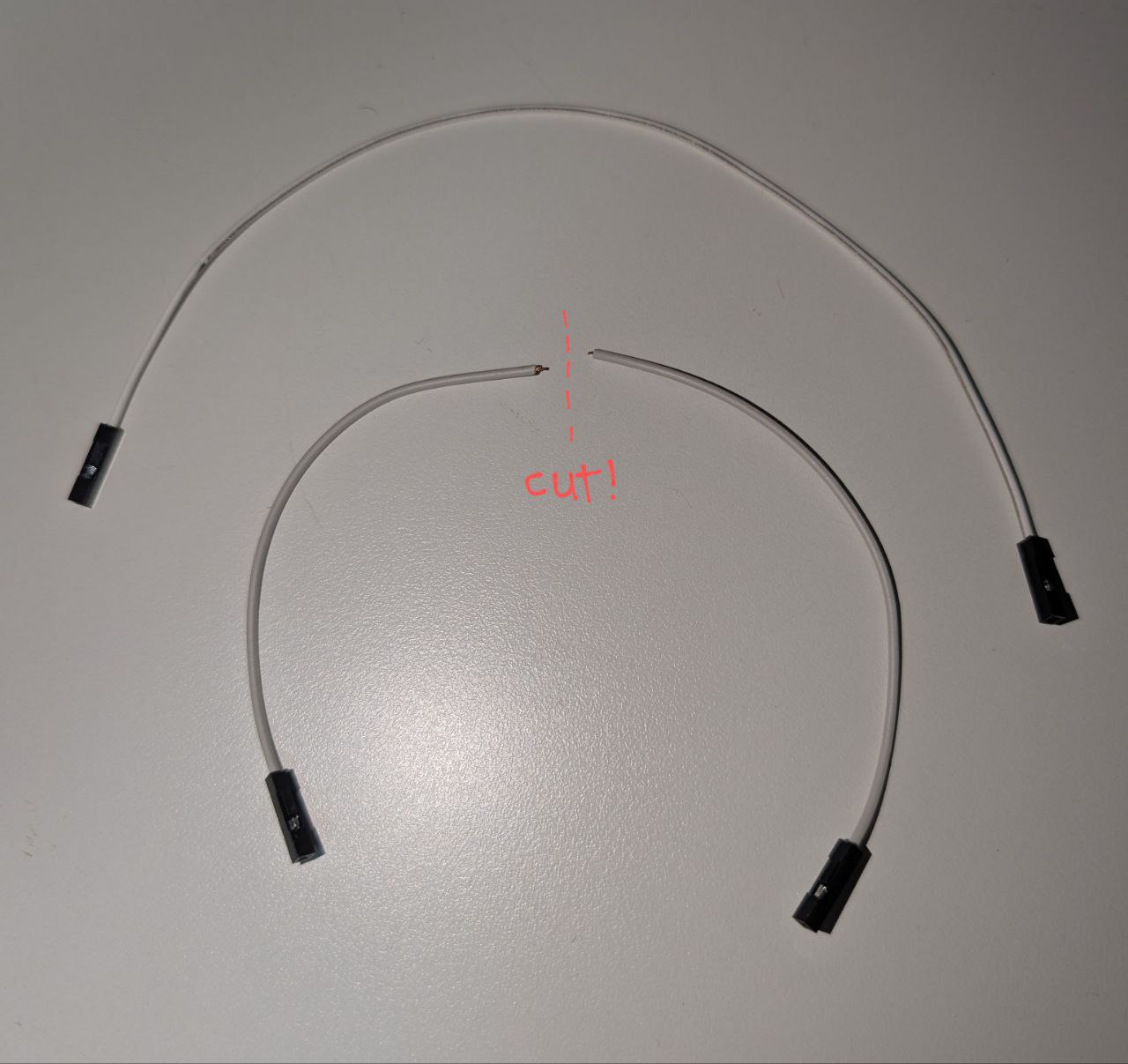

Previously, we were able to read/write the EEPROM of the RP2040 since it was directly wired to RP2040 which we had access to.

However, how do we now access the EEPROM of the STM32 when there is no direct connection from the RP2040?

We can make the connection ourselves!

Despite only being provided female-to-female jumper cables, we can cut the jumper cables to expose the wires.

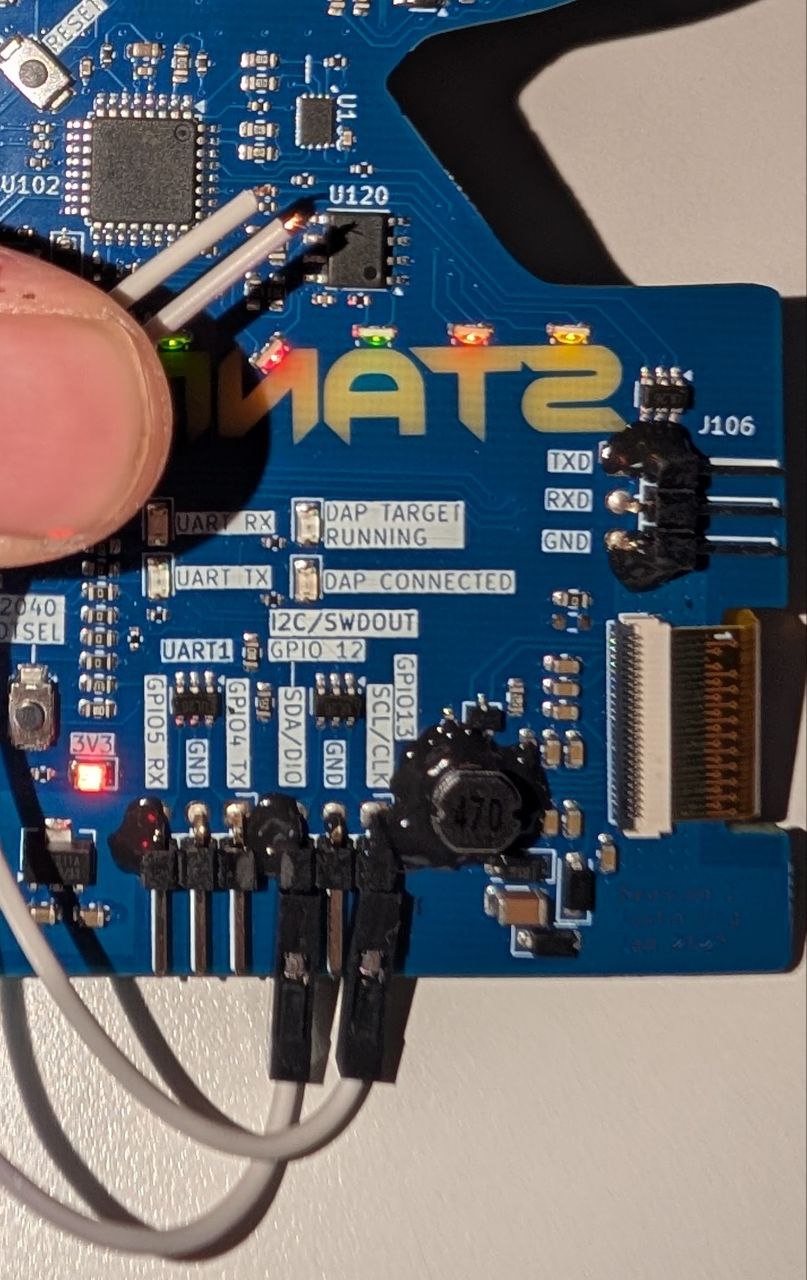

Afterwards, in order to establish the I2C communication with the EEPROM, we can connect our RP2040 SDA/SCL to the corresponding pins in the EEPROM.

how?

While pressing the wire to the SDA and SCL pins of the EEPROM, we can run the following script to continuously scan and write our data structure to the EEPROM as soon as we make a connection.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

from machine import I2C, Pin

import time

EEPROM_ADDR = 0x50

def read_24c01(mem_addr, num_bytes):

i2c.writeto(EEPROM_ADDR, bytearray([mem_addr]))

return i2c.readfrom(EEPROM_ADDR, num_bytes)

def write_24c01(mem_addr, data):

i2c.writeto(EEPROM_ADDR, bytearray([mem_addr]) + data)

# keep scanning because its unreliable to manually stick the wire to the PIN :p

while True:

i2c = I2C(0, sda=Pin(12), scl=Pin(13), freq=100000)

res = i2c.scan()

time.sleep(1)

if res:

write_24c01(0x0, bytes([42, 0, 255, 102]))

print(read_24c01(0x0, 1000))

Afterwards, when we try to validate again in our UART menu, we get the flag

1

2

> validate

congrats: flag{i_c_WhA7_y0u_d1d_th3Re}

What’s in the teapot

We are given yet another program to interact with for this challenge.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

bool challenge_tea_run(char *ret) {

HAL_StatusTypeDef status;

HAL_GPIO_WritePin(FLASH_SS_GPIO_Port, FLASH_SS_Pin, GPIO_PIN_RESET);

uint8_t tx_buffer[] = {0x48, 0, 16, 0, 0};

status =

HAL_SPI_Transmit(&hspi2, tx_buffer, sizeof(tx_buffer), HAL_MAX_DELAY);

if (status != HAL_OK) {

strcat(ret, "internal comms error (1)\r\n");

return false;

}

uint8_t d[16] = {0};

status = HAL_SPI_Receive(&hspi2, d, sizeof(d), HAL_MAX_DELAY);

if (status != HAL_OK) {

strcat(ret, "internal comms error (2)\r\n");

return false;

}

HAL_GPIO_WritePin(FLASH_SS_GPIO_Port, FLASH_SS_Pin, GPIO_PIN_SET);

uint32_t tea_leaves[4] = {

(uint32_t)(d[0] << 24) | (d[1] << 16) | (d[2] << 8) | d[3],

(uint32_t)(d[4] << 24) | (d[5] << 16) | (d[6] << 8) | d[7],

(uint32_t)(d[8] << 24) | (d[9] << 16) | (d[10] << 8) | d[11],

(uint32_t)(d[12] << 24) | (d[13] << 16) | (d[14] << 8) | d[15]};

char flag[] = FLAG_CHALLENGE_TEA;

static_assert(sizeof(flag) % BLOCK_SIZE == 1,

"flag must be multiple of BLOCK_SIZE");

size_t len_flag = strlen(flag);

for (size_t i = 0; i < len_flag; i += BLOCK_SIZE) {

encipher((uint32_t *)&flag[i], tea_leaves);

}

strcat(ret, "You swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\n");

char tmp[8];

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < sizeof(flag) - 1; i++) {

snprintf(tmp, sizeof(tmp), "%02x", flag[i]);

strcat(ret, tmp);

}

strcat(ret, "\r\n");

return true;

}

It reads a 16-byte key from some SPI flash storage and encrypts the flag with it. It then prints the encrypted flag out.

The SPI interface utilizes these 4 pins to function

- SCLK (Serial Clock)

- synchronize data transfer.

- MOSI (Master Out, Slave In)

- used for communication from the master to the slave.

- MISO (Master In, Slave Out)

- used for communication from the slave to the master.

- CS (Chip Select) / SS (Slave Select)

- control signal used to select a specific slave device

I had the idea of connecting MISO to GND such that all the data that it reads from the SPI flash will be null bytes which allows us to easily decrypt the flag.

Once again, by cutting my jumper wire and connecting loose wire to the pin of the SP1 flash, I was able to obtain what I thought was the flag encrypted with 16 null bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nf143193e133a1aa12df99f2a7f8dca5f9d321f319f3f9e44bb70982e111f99e9\r\n> '

b'pour\r\nYou swirl the teapot before pouring out...\r\n\r\nac6a42ada694872b2de61be87f1d001a4aaf5cc06afbaf2c01d244698cdb8533\r\n> ' # connected GND to MISO

However I was not able to successfully decrypt it and did not obtain the flag for this :P

Conclusion

Overall, this is my favourite #BadgeLife experience yet since I was able to fully appreciate the intricacies of the hardware without being stumped by the barrier of not owning any other hardware tools. It was beautiful how we were able to use the badge to talk to itself and solve the challenges.

Huge thanks once again to Justin for the awesome badge and the guidance as well :)

Till next time~