Breaking Disassembly — Abusing symbol resolution in Linux programs to obfuscate library calls ️🎭

Summary

This research will dive into how symbol resolution works (in ELF), and how common tooling such as decompilers and disassemblers parses the symbol resolution metadata to identify imported/library functions. Finally, we will see how we can easily modify some of these metadata to break such tools while maintaining the full functionality of ELF programs.

The scripts and POCs mentioned in this post can be found here.

This is a (hopefully) novel obfuscation technique that I’ve not seen in the wild before that is rather easy to do. More importantly, this was a fun discovery and helps us to gain insights into how our tools work (and the potential pitfalls).

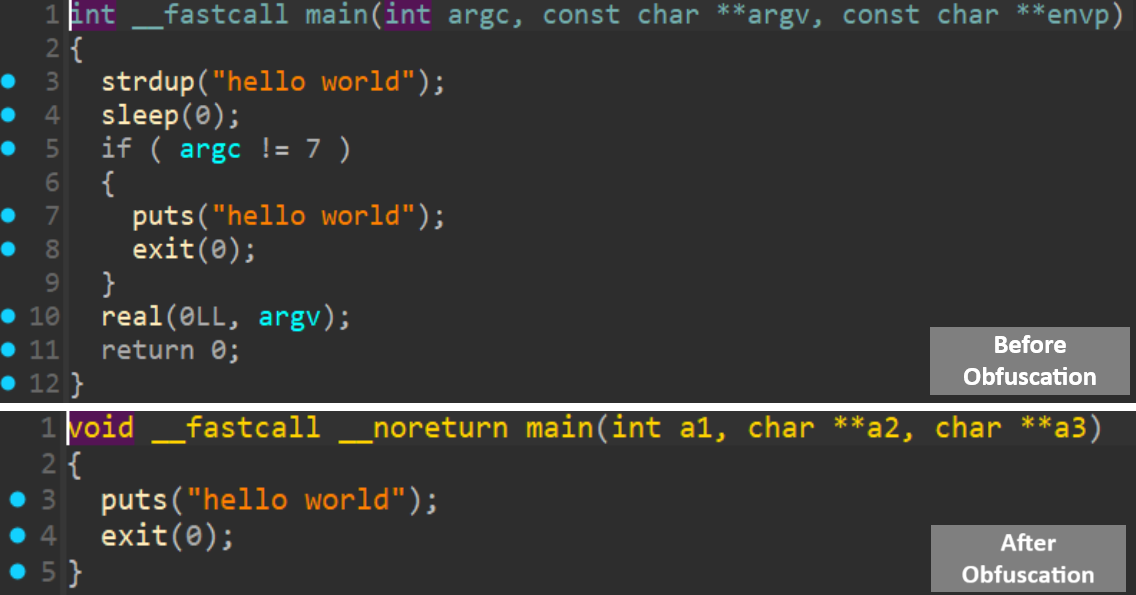

Here’s a sneak peek as to what the proof of concept would look like in a decompiler.

As you can see, we were able to make strdup show up as puts, and sleep show up as exit, without actually changing the functionality of the program (trust me XD), allowing us to hide the main functionality of the program behind a simple hello world program.

What is Symbol Resolution?

Before we dive into the internals of how it works, let’s first understand the background by talking about what is symbol resolution and why we need it.

Executable files can make reference to entities which are not defined inside themselves. For instance, variables or procedures on shared libraries. Those entities are identified by external symbols. The executable might as well have internal symbols that can be referenced by external files – as is the case, of course of libraries.

Symbol resolution, in this context, is, once a program has been loaded into memory, assigning proper addresses to all external entities it refers to. This means changing every position in the loaded program where a reference to an external symbol was made.

These addresses will depend on where, in the memory, the code with the external symbols has been loaded.

To put this into context, let’s walk you through how this would look like in an ELF program.

Whenever we call library functions in our program, the assembly/machine code for this function typically resides in an external shared library (i.e. common C library functions can be found in libc.so.6) that is loaded into memory when a program is executed.

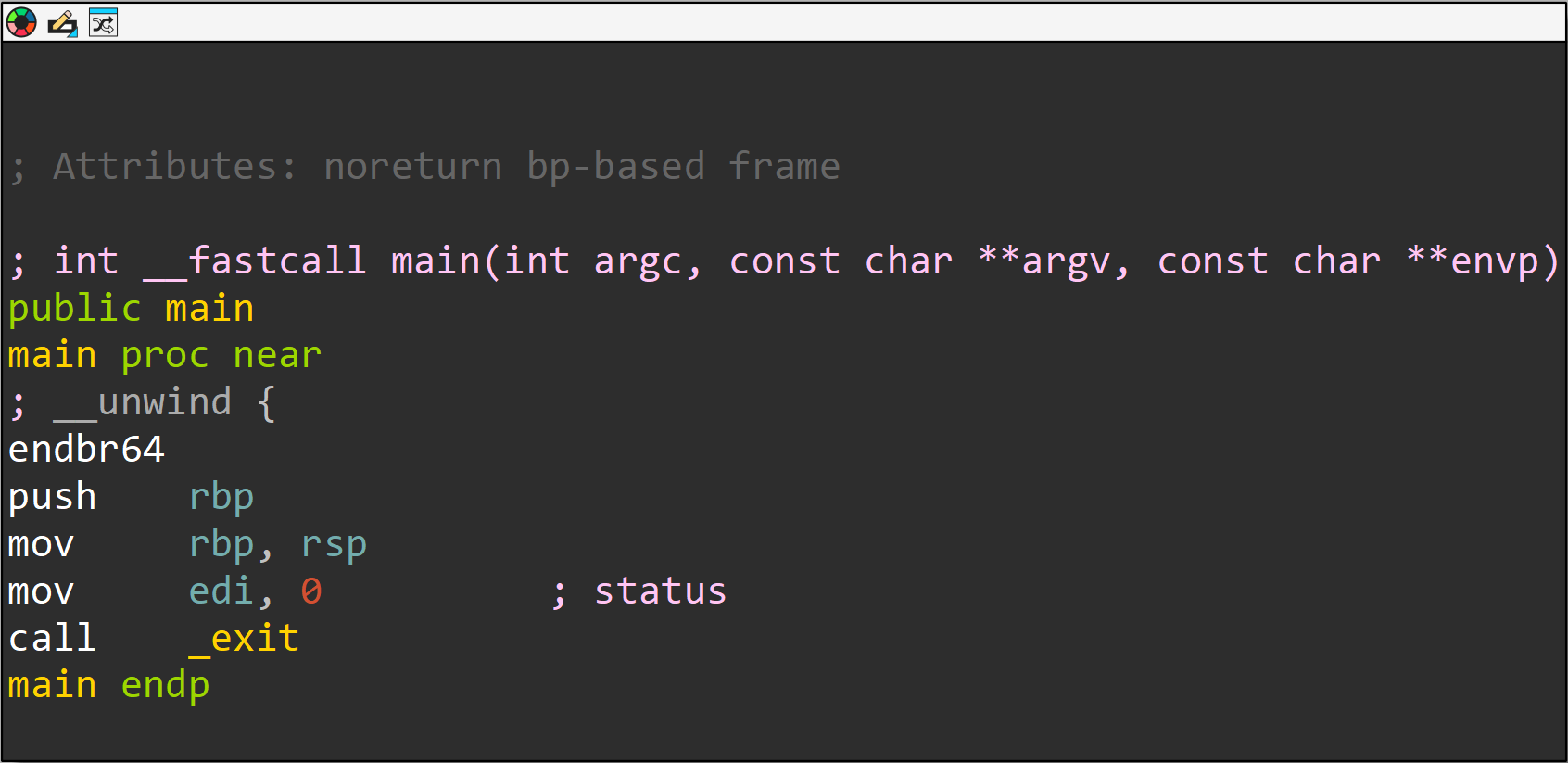

Due to ASLR, this shared library is loaded at a random address on every run of the program.

memory mapping of /bin/cat at runtime

memory mapping of /bin/cat at runtime

As such, before we can call library functions, we will first need to resolve the address of these library functions at runtime.

Where do resolved symbols go? (GOT)

All external library functions that are required by a program will have an entry in a function table called Global Offset Table aka GOT.

At the start of the execution, this table will start with holding an address to the symbol resolution dispatcher (more on this later). After a function address has been resolved, it will be saved into its corresponding GOT entry such that it will not need to be resolved when called again later.

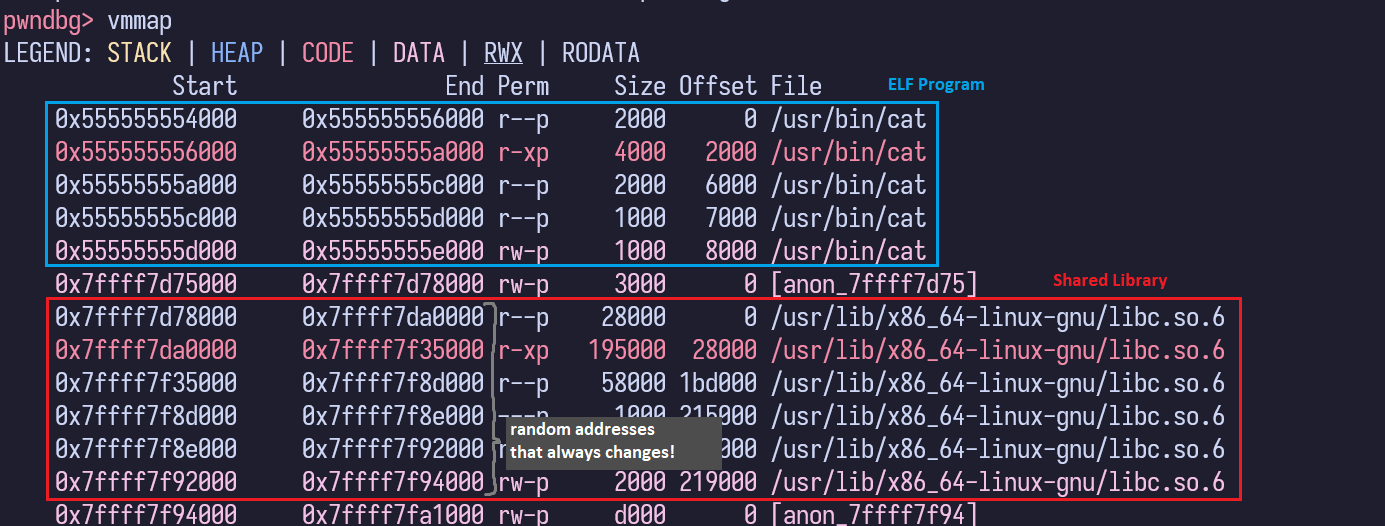

Here is what the GOT would look like for a program with two functions puts and exit. In this example, puts has been resolved but exit has not yet been resolved (and hence still holding an ELF address).

inspecting the global offset table in memory

inspecting the global offset table in memory

When are symbols resolved? (RELRO)

Depending on the Relocation Read-Only (RELRO) security protection of the program, the program will either choose to resolve the functions only when it is used for the first time (aka Lazy Binding) or on program startup (aka Eager Binding).

Eager Binding is when all symbols are resolved on program startup. This is the case when there is Full RELRO. This seems to be the default behavior for compilers nowadays (reduce exploit vectors), but causes program startup to be slower.

Lazy Binding is when symbols are are resolved when it is called for the first time. This is the case when there is No RELRO or Partial RELRO.

Regardless, the timing of when the symbols are resolved do not matter to us, as the symbols will still have to be resolved at runtime.

How are symbols resolved?

We will walk through the process of how the different pieces/metadata of our program helps the linker to resolve a function address.

The Procedure Linkage Table

The Procedure Linkage Table (aka plt) contains small instruction stubs that help resolve library functions or call the absolute addresses of library functions from the respective GOT entry.

I highly recommend checking out this graphic that explains how the PLT and GOT work.

Let’s take a look at what actually happens when an ELF program tries to call puts function.

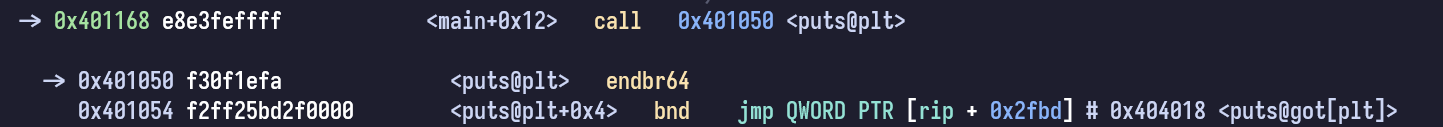

call puts@PLT which dereferences and jumps into GOT entry

call puts@PLT which dereferences and jumps into GOT entry

As you can see, when we call puts, it actually calls puts@PLT which attempts to dereference and jump into its own GOT entry. If the symbol has already been resolved before, the GOT entry of puts would contain its libc address.

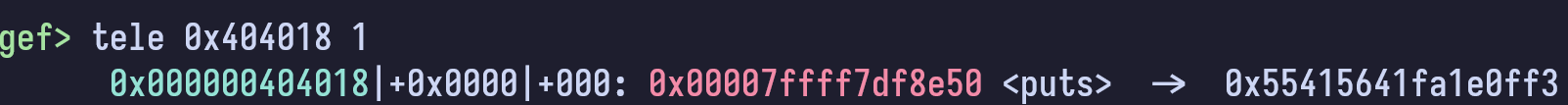

puts@GOT after puts has been resolved

puts@GOT after puts has been resolved

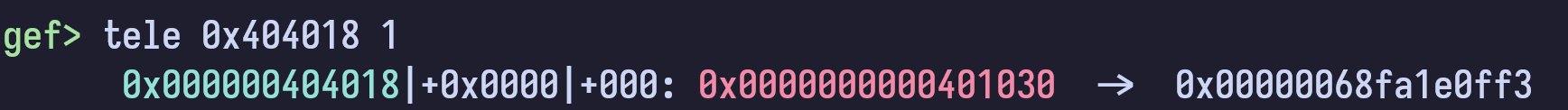

puts@GOT if puts is not resolved

puts@GOT if puts is not resolved

Naturally, we are more interested in what is in 0x401030 (the value in the GOT if it is not resolved) and how it resolves our library function.

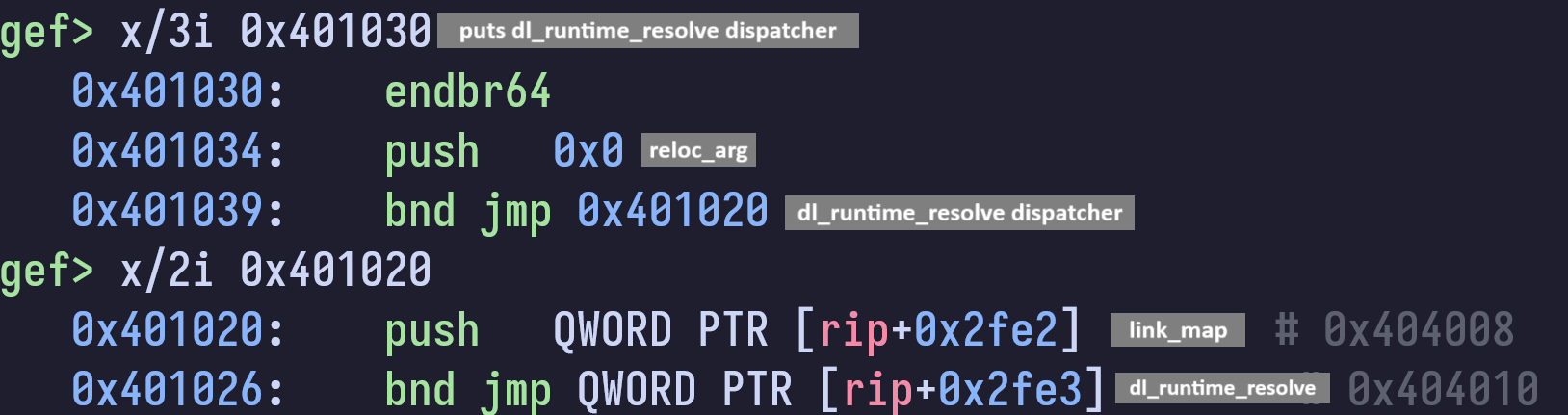

push some arguments before calling dl_runtime_resolve

push some arguments before calling dl_runtime_resolve

The PLT ultimately calls dl_runtime_resolve(link_map, reloc_arg=0) which will resolve the puts symbol, save it into its GOT entry, and call it. Without diving further into the source code and runtime resolve internals, I will attempt to give a high level overview of how the different metadata in our program is used by this function to resolve our symbol.

The link_map struct contains information for loaded shared objects including the difference between the address in the ELF file and memory addresses, the absolute file name, a pointer to the dynamic section, and a chain of loaded objects using next and prev pointers. It is used by the debugger and dynamic linker to manage shared libraries in memory.

High-level overview of the runtime resolver

If you are interested in the dl-runtime internals, I highly recommend this blog post that dives into the source code and how it works.

It goes into much more details of everything about the resolver that I’m about to talk about, and also goes through how you can fake your own metadata to resolve arbitrary functions as an exploit technique!

Structures

JMPREL (.rela.plt)

This sections contains information used by the linker to perform relocations. It is composed by 0x18-byte aligned Elf64_Rel structures.

Think of it as an array of the following Elf64_Rel struct, where each struct corresponds to an external function.

This is accessed by the resolver via JMPREL[reloc_arg].

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef uint64_t Elf64_Addr;

typedef uint64_t Elf64_Word;

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Addr r_offset; /* Address/Offset of GOT Entry */

Elf64_Word r_info; /* Relocation type and symbol index */

} Elf64_Rel;

SYMTAB (.dynsym)

This is accessed by the resolver via SYMTAB[rela->r_info >> 32]

SYMTAB stores symbol information/metadata in the following struct:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Word st_name ; /* Symbol name (string tbl index) */

Elf64_Addr st_value ; /* Symbol value */

Elf64_Word st_size ; /* Symbol size */

unsigned char st_info ; /* Symbol type and binding */

unsigned char st_other ; /* Symbol visibility under glibc>=2.2 */

Elf64_Section st_shndx ; /* Section index */

} Elf64_Sym ;

STRTAB (.dynstr)

Contains the name of the external symbols that needs to be resolved.

Piecing it together

To summarize how the resolver parses the metadata to resolve the function,

- Retrieve JMPREL entry for function -

jmprel_entry = JMPREL[reloc_arg] - Retrieve SYMTAB entry for function -

symtab_entry = SYMTAB[jmprel_entry->r_info >> 32] - Retrieve function name -

func_name = STRTAB[symtab_entry->st_name] - Looks through the loaded libraries to find a match for the function name.

- Parse the library that is found to find the absolute address of the function.

- Save the resolved address into

jmprel_entry->r_offset(the GOT entry for the function)

There is slightly more validation and necessary values from the metadata mentioned above, however those are not as important hence the details are omitted.

Confusing the Disassembler

Now that we know how the different metadata values are used to resolve an external function, we can play around with the values to see how the program and our disassembly tools will behave.

Spoofing reloc_arg values

By modifying the reloc_arg of a function A’s PLT stub to push the reloc_arg of function B, this will cause function A to actually act as function B while making the disassembly look the same.

Let’s look at the following poc binary.

Looking at the function indexes of the JMPREL table, we can patch exit->sleep and alarm->exit to make the disassembly terminate early.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

exit(0); // patched reloc_arg to act as sleep

puts("hello world!");

alarm(0); // patched reloc_arg to act as exit

sleep(0); // we leave this inside just to include it as an import

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

; ELF JMPREL Relocation Table

0 Elf64_Rela <404018h, 200000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT puts

1 Elf64_Rela <404020h, 300000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT alarm

2 Elf64_Rela <404028h, 500000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT exit

3 Elf64_Rela <404030h, 600000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT sleep

LOAD ends

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

.plt:0000000000401040 endbr64

- .plt:0000000000401044 push 1 // alarm reloc_arg

+ .plt:0000000000401044 push 2 // exit reloc_arg

.plt:0000000000401049 bnd jmp sub_401020

.plt:0000000000401050 endbr64

- .plt:0000000000401054 push 2 // exit reloc_arg

+ .plt:0000000000401054 push 3 // sleep reloc_arg

.plt:0000000000401059 bnd jmp sub_401020

1

2

$ ./poc_reloc_arg

hello world!

Flaws

- Modifying the

reloc_argchanges the underlying functionality of the program instead of the appearance of the disassembly. This makes it hard to obfuscate as we would need to modify the compilation process as to ensure the obfuscated binary will do what we want. - If we swap function A and function B, function A will act as function B vice versa. However, the first call of function A will resolve function B’s GOT. Once function B’s GOT is resolved, both function A (still unresolved and has function B’s reloc_arg) and function B (resolved) will act as function B.

Nevertheless, a sufficiently determined person might be able to abuse this flaw to further make it difficult to trace the functionality of a function since a single function can do two different things depending on whether its GOT has been resolved or not.

Writing resolved pointers to unused GOT entries

Another observation I made was that the disassembler would identify the library function based on its corresponding jmprel_entry->r_offset aka where the resolved pointer is written to.

Let’s look at the following poc binary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

// gcc -Wl,-z,relro,-z,lazy test.c -o poc_r_offset

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

sleep(0); // shows up as exit(0)

puts("hello world!");

exit(0);

}

void* __attribute__((used)) dummy() {

void* a = malloc(0);

return a;

}

I have patched the following JMPREL entries.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

LOAD:0000000000000670 Elf64_Rela <4018h, 300000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT puts

- LOAD:0000000000000688 Elf64_Rela <4020h, 500000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT malloc

- LOAD:00000000000006A0 Elf64_Rela <4028h, 600000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT exit

- LOAD:00000000000006B8 Elf64_Rela <4030h, 800000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT sleep

+ LOAD:0000000000000688 Elf64_Rela <4028h, 500000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT malloc

+ LOAD:00000000000006A0 Elf64_Rela <4030h, 600000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT exit

+ LOAD:00000000000006B8 Elf64_Rela <4020h, 800000007h, 0> ; R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT sleep

Effectively, we have shuffled our GOT entries to appear as such:

| Actual function called | GOT entry it is saved into (and also the function it shows up as in a disassembler) |

|---|---|

| malloc | sleep |

| exit | malloc |

| sleep | exit |

This generates the same disassembly as before

1

2

$ ./poc_reloc_arg

hello world!

As for why we needed to add the malloc function into the program even though it was not used, this was to make an extra entry in GOT that we can use. Read the flaws below to understand why this is necessary.

Flaws

- We cannot have multiple functions with the same

r_offsetvalue as it would raise an error in the disassembler. - If we swap the

r_offsetof two functions, function A will resolve itself into the GOT entry of function B. Subsequent calls to function B will call function A instead which might cause a segmentation fault.

Nevertheless, this is slightly easier to use than modifying the reloc_arg since we are now only ‘faking’ the disassembly without changing the functionality of the program (if we ignore flaw 2).

Insight of how the Disassembler works

Based on the previous observations, the likely hypothesis as to how the disassembler might resolve symbols would be

- Identify functions in

.pltthat simply jumps into GOT entry.1 2

endbr64 bnd jmp cs:off_404028 // some GOT entry

- Parse JMPREL and SYMTAB entries to find

jmprel_entry->r_offsetthat matches GOT entry1

Elf64_Rela <404028h, 400000007h, 0> ;

- Find corresponding

symtab_entry = SYMTAB[jmprel_entry->r_info >> 32]to obtainsymtab_entry->st_name(in this case, symtab index is 4)1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

ELF Symbol Table 0 Elf64_Sym <0> 1 Elf64_Sym <offset aLibcStartMain - offset unk_400460, 12h, 0, 0, 0, 0> ; "__libc_start_main" 2 Elf64_Sym <offset aPuts - offset unk_400460, 12h, 0, 0, 0, 0> ; "puts" 3 Elf64_Sym <offset aStackChkFail - offset unk_400460, 12h, 0, 0, 0, 0> ; "__stack_chk_fail" 4 Elf64_Sym <offset aPrintf - offset unk_400460, 12h, 0, 0, 0, 0> ; "printf" // THE FUNCTION IS printf! 5 Elf64_Sym <offset aGmonStart - offset unk_400460, 20h, 0, 0, 0, 0> ; "__gmon_start__" ELF String Table

As you can tell, the disassembler identifies the function based on where the resolved function address is written to (by right, into its own GOT entry!)

It does not consider other metadata such as reloc_arg or what happens if there is a mismatch between the GOT entry that the PLT jumps into versus the GOT entry that it saves the resolved address into. This allows us to easily confuse the disassembler to identify the wrong library functions.

Bonus: Fixing the flaws

We have mentioned 2 ways we can modify the program metadata to confuse the disassembler. However, both methods has the same problem whereby functions might write into each other’s GOT causing unintended behaviors.

There is actually one cool modification we can make to our program to modify this behavior such that resolved pointers are NEVER written back into the GOT, allowing us to abuse the resolver as much as we want.

We can write a program that sets this environment variable and execv itself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

LD_BIND_NOT (since glibc 2.1.95)

If this environment variable is set to a nonempty string,

do not update the GOT (global offset table) and PLT

(procedure linkage table) after resolving a function

symbol. By combining the use of this variable with

LD_DEBUG (with the categories bindings and symbols), one

can observe all run-time function bindings.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// we still need to ensure partial/no RELRO

// gcc -Wl,-z,relro,-z,lazy ld_bind_not_poc.c -o ld_bind_not_poc.elf

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if (!getenv("LD_BIND_NOT")) {

setenv("LD_BIND_NOT", "hehe", 1);

execv(argv[0]);

}

sleep(0);

puts("hello world");

exit(0);

}

This essentially sets the LD_BIND_NOT variable (if it is not already set) before running the rest of the program, ensuring that the symbols remain unresolved.

Writing an Obfuscator

The Idea

In the section above, we discussed ways that we can modify the symbol resolution metadata to result in false disassembly. The easiest way to obfuscate a program’s import would be to write the resolved pointer to the GOT entry of unused functions. The end goal is to be able to take in a compiled program, and output an obfuscated program that has the exact same functionality as the original program.

Here’s the strategy

- We identify the list of X number of library functions that is used by the program

- We find another random X number of library functions (likely we can parse the libc for it?) that are not used by the program, and add it to the program

- We map each of the used library function to a random unused library function and update the

jmprel_entry->r_offsetaccordingly.

Sounds simple right? However, adding imports to a compiled program is more tricky that I thought. We would need to manually add in SYMTAB, STRTAB, DYNSYM, .got, .plt entry into the program for the corresponding import. We would also need to fix all the program offsets to account for the additional metadata that we added into the program.

Please reach out if you find a way to reliably implement the above 👀

The Scuffed Result

Instead, I asked Claude to generate me a huge .h file that imports as many functions as possible (i couldn’t find any way to parse the libc for exported functions and generate a header file with them). This ended up looking like this.

- Compile your program without the header file once with the following

gccflags:-Wl,-z,relro,-z,lazy(ensure partial relro) - Run

get_imports.pyto get the list of imported functions. - Now that we have a list of the functions used by the program, we can re-compile the program with the header file by adding

#include "relfuscate.h".- You might need to add some libraries when compiling depending on the random functions that you have in your

relfuscate.h. The one provided above would require-lm -ldl -lpthread -lcrypt -lrt -lutil -lresolv -lnsl -lselinux -lcrypto. (p.s. you should also add-wto supress warnings for your sanity!)

- You might need to add some libraries when compiling depending on the random functions that you have in your

- To remove the unnecessary code, you can run

objcopy --remove-section ".fun" program.elf - Now we will run

relfuscate.pyand paste the list of imported used functions obtained fromget_imports.py, and we are done!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

❯ python3 ../relfuscate.py test_with_header test_with_header_relfuscated

Paste the list of library functions the binary uses: ['puts']

Functions considered 'used': ['puts']

ELF File: test_with_header

Architecture: 64-bit

------------------------------------------------------------

puts -> mallopt

gtty -> mempcpy

fesetround -> sinhf

lrintf -> times

endgrent -> llogbl

lgammal_r -> lgammaf

# ... truncated ...

Applying modifications...

Successfully created modified file: 'test_with_header_relfuscated'

There is definitely much work that can be done to improve this script, feel free to make a pull request if you have any ideas or time!

The Conclusion

Ultimately, this would make every single API function appear incorrectly and might even have other implications that might further deter reverse engineering efforts:

- Decompiler might refuse to decompile due to incorrect call types (if the fake function requires many more arguments that the original function)

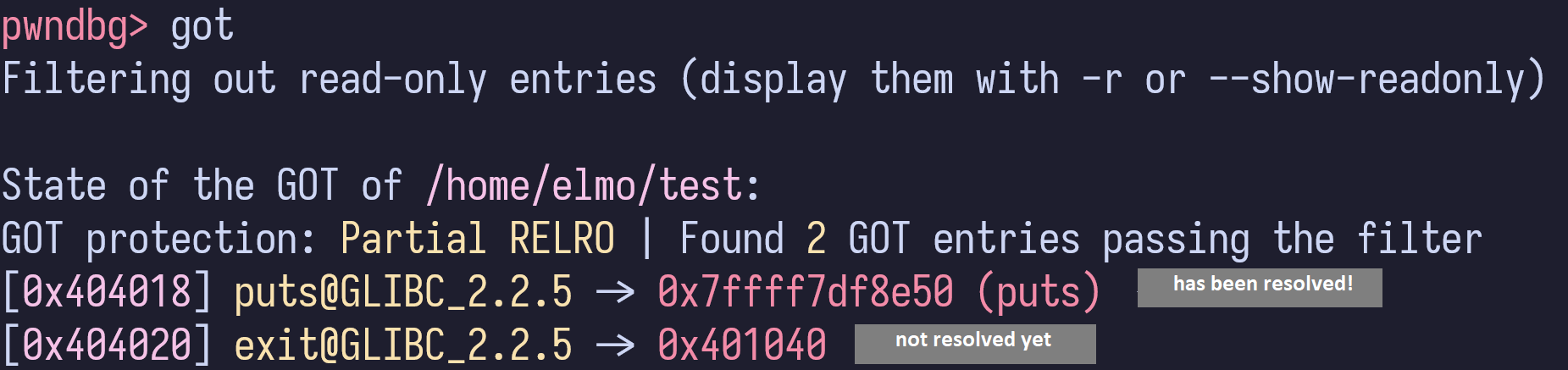

- Disassembler might stop disassembly early if it encounters a

noreturnfunction (i.e. exit, _exit, abort).

You can find the obfuscation scripts and test files here.

Deobfuscation is easier o_o

At the end of the day, in order for the program to still run with the intended functionality, there has to be some truth in the program that can allow us to still identify the correct API calls and deobfuscate the program.

We can write a script to parse all the PLT stubs and JMPREL entries (just like how the linker does the symbol resolution) to fix the r_offset metadata and reflect the correct API call.

In the interest of my time (and all the work I’ve been avoiding), I shall leave this as homework for the reader 😝

R3CTF Challenge

I wrote a reverse engineering challenge for r3kapig’s CTF using this technique.

It implemented a maze generation algorithm based on the SHA256 hash of the contents of the ELF in memory, expecting participants to deobfuscate the broken function calls, bypass the anti-debugging checks to generate/replicate the maze and finally solve it.

You can find the challenge here.

Conclusion

The obfuscator script that I wrote is merely the tip of the iceberg and one that is easy to use. With enough effort, I believe that the APIs can be remapped in a much more compliacted way.

Exploring new ways to breaking disassembly/decompilation and deter reverse engineering has been an area of interest for me recently. This interest is fueled by the rise of LLMs and MCPs that has made traditional reverse engineering of unobfuscated binaries much more trivial, making obfuscators more necessary than before if you want to avoid prying eyes.

I hope you enjoyed this post! If it interests you, you can check out some of the other CTF challenges that I’ve written in the past here (including some other cursed obfuscated challenges).

Thanks to goatmilkkk for proofreading!